The bitterness of poor quality remains long after the sweetness of low price is forgotten.

Well done is better than well said.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790)

Purchasing woodworking cutting tools long-distance based only on pictures, what you read online, and retailer’s vague descriptions can be confusing and frustrating. And squawking BS meters are not reassuring.

In this post, with Gentle Reader’s kind indulgence, your most humble and obedient servant will share some insight to help Gentle Reader avoid the most common mistakes.

If the following is obvious please do not be offended. I am confident our discerning and intelligent Gentle Readers will discover somewhere in this post what is called in Japan a “stork in a rubbish dump 掃き溜めに鶴,” which perhaps translates better to a “Jewel in a garbage pile.” I trust there are more jewels than rubbish to be found in this article.

Risks & Psychology

At C&S Tools we understand the risks and stresses inherent in long-distant purchases. After all, not much can be discerned about a cutting-tool’s quality or performance from online photos and retailer’s product descriptions alone. We believe the best way to reduce uncertainty, alleviate customer’s concerns and calm BS alarms is to treat customers the way we want to be treated.

The difficulty faced by the consumer in assessing the quality of woodworking blades based on photos and generic descriptions alone, combined with the curiously short-sighted tendency of many consumers nowadays to demand lowest possible price without considering the consequences to quality and performance, has created a strange psychological syndrome we call “Chinese Logic.”

The mental mathematics those inflicted with this disease feverishly and endlessly reiterate goes something like this: “Product A looks identical to Product B in the photos, but B is 1/3 the price, so B must be better.” Makes perfect sense, right?

In our professional experience, most corporate procurement processes, as well as those of many private individuals, wallow ass-up in this shallow logic, but whether corporate or private, construction or real estate, the results are almost always stinky and embarrassing.

But wait a minute, as Lieutenant Columbo always mumbles, could Chinese Logic be valid? After all, we live in a Wally World where most products readily available to the consumer are labeled “Made in China,” so let’s follow the math a little further. Given a choice between Turd A, sorry, I mean Product A, made in an unnamed automotive bumper factory located in Southern Guangzhou by untrained farmers (not blacksmiths), and Product B, made in a mystery manufactory located just outside Shanghai where untrained farmer’s wives (not blacksmiths) normally sew decorative cushions with embroidered images of darling kittens, puppies, and ducklings, the only discernible differences between the two products will be their outward appearance in photos, and price. Tragically, real physical quality is seldom included in these calculations, leaving the consumer with only perceived quality rattling around noisily inside his head, cushioned by smelly patties of marketing BS, of course.

If the consumer doesn’t care about performance and intends to use, toss and replace said turd, sorry, I mean “product,” in a short time anyway, no big deal. But given time and enough repetition could this experience have a Pavlovian doggie drool effect on consumer’s buying habits and maybe even their psychology? You bet your sweet bippy it could.

Of course I’m safe from such mind conditioning because of my most excellent tinfoil cap with its projecting curly copper wires and red fringe (I’ve added a groovy red ball fringe recently to confuse those pesky alien drones that follow me everywhere), but I worry about thee. >~(ツ)~<

When, however, the desired product is not a pretty polyester pillow embroidered with adorable yellow ducklings, but a decidedly un-cuddly cutting tool such as a chisel or plane blade, the wise man will immediately realize that, if the choice before him is either Turd A or Turd B, he needs to find better options, none of which will involve car bumpers, embroidered pillows or Chicom ordure. The fact that Gentle Reader is bothering to read this article is clear evidence of his superior intelligence and grasp of these principles (ツ)。

BTW, none of our products or their component parts are made in China. Indeed, everything from the steel in the blades to the wood in the handles and blocks, and even the hoops are made in Japan by Japanese craftsmen. Everything. No exceptions.

Assess the Retailer

Sorry to digress. I almost fell off my soapbox and kinked some wires on my most excellent hat! (ツ)

The real-world performance of a woodworking blade depends little on outward appearance, and not at all on cheap talk or even pretty pictures, but almost entirely on the crystalline properties of the steel that makes up the blade, properties resulting directly from the skill of the blacksmith (or factory in the case of most other retailers) in forging the blade and heat-treating the steel, properties that can be confirmed only through actual use. So it’s no wonder people have a hard time telling jewels from rubbish.

A few of the practical difficulties we must overcome when attempting to buy quality woodworking cutting tools long-distance include the following:

- It is impossible to judge the crystalline quality of steel and the quality of a blade lamination in tools from photos on websites or in catalogs alone;

- It is impossible to judge the crystalline quality of steel by simply holding a tool; One must actually use it hard and sharpen it a few times;

- Many marketing claims are unreliable because, even if they are not fantastically optimistic misrepresentations spun to increase profits, they are written by shopkeepers and/or people in marketing departments that have never used a blade except to maybe cut a sandwich or open a box of printer paper. They couldn’t accurately discern the quality of steel in a chisel even if they sat on it… For a long time… And wiggled around. So as a wise consumer we must assess the veracity of the retailer’s claims for ourselves.

- Most online retailers offer no real warranty, and even if they do, the customer ends up paying all the costs required to benefit from it, an expensive proposition internationally. When considering any purchase, much less a long-distance one, wisdom urges us to select a retailer willing to repair or replace defective tools. And we need him to pay the shipping costs should his tool prove to be at-fault.

If we can’t reliably assess the quality and/or value of woodworking tools long-distance, the next-best option is to assess the seller and his warranty. Here’s a few common-sense suggestions:

Read the retailer’s product description and information carefully and ask questions. Beware of retailers who provide only sketchy information lacking details and who won’t or can’t answer your pertinent questions, for there’s usually a reason they can’t or won’t beyond being too busy making money to provide proper customer service.

Understand the source of the information being provided. There are exceptions, of course, but most websites selling tools take a blurb from the wholesaler’s or distributor’s marketing people, dress it in a short skirt and high heels, and trot it out curbside. Sometimes they trip on those heels exposing their spotty unmentionables. How embarrassing! Often the information they put out has a peculiar odor you can detect if you pay attention. We recommend you look for first-hand, accurate information from knowledgeable, experienced, responsible people without hairy legs wobbling on high heels, spotted undies, or BO, instead of the clickbait guys on BoobTube bragging in their ignorance.

Understand the retailer’s practical experience with the tools, because this will help you assess the veracity of his claims. Does the fella selling the tools or the person recommending a particular tool or brand of tool to you have personal experience with that tool or brand, or are they just an e-commerce puke parroting claims by a wholesaler or distributor who, like him, has no direct experience beyond marketing, and maybe sitting on, chisels or planes?

Here are some questions you might ask: Have they cut mortises with the chisels they sell? Have they planed beams with the handplanes they sell? Have they cut kumiko panels with the saws they sell? How many times have they sharpened, by hand, the tools they sell? What angle did they sharpen the blade to? How did the tool perform when it struck a knot? What steel was used? Is the blacksmith an individual craftsman or group of craftsmen with direct responsibility for quality, or just a factory? Most stories cobbled together by marketing czars or e-commerce pukes will begin to rattle apart at this point.

Be Knowledgable. If you don’t have it already, you will need to gain some knowledge on the subject yourself to enable you to ask relevant questions, ascertain the retailer’s level of knowledge and experience, the truth of his claims, and the suitability of his tools to your needs. This means finding and studying valid sources of information.

At C&S Tools we provide reliable information, without smoke and mirrors, to help buyers make wise decisions. For free. We reveal who we are and what our experience is. We have used similar tools as a woodworking professional for many years, purchase and physically stock the tools we carry with our own money (no gifts or freebies) and have personally tested them to destruction, so we can share valid, useful opinions. We will provide details and helpful guidance instead of the usual corporate silence or marketing department tripe.

Seek relevant recommendations from experienced people who know what they are talking about. Whenever possible seek the advice and recommendations of friends or people you trust who have direct, hands-on experience with the tools sold by the retailer in question, not just some guy sitting in his Mom’s basement trying to justify his own tool purchase and desperate for company in his misery.

Beware of advice from the guy who claims to have decades of experience, but actually bought his first Japanese tool only 3 years ago and has never been paid a dime for using it. Yes, there are too many of those “experts” out there.

Beware the trolls and orcs on the forums. The amount of truly useful information and advice to be found in those roiling, flyblown cesspits is too little to measure.

The experiences and opinions of our customers recorded in our “Testimonials” page may be helpful.

Make sure the retailer provides a valid guarantee, one that won’t cost you money to benefit from. More on that below.

The Warranty

We do our best to follow the ancient principle Benny Franklin puts forth in his saying quoted above: “Well done is better than well said.”

Before you lay down your money, make sure the seller has a real guarantee, not just hot air, for defective materials and workmanship just in case the tool turns out to be more rubbish than jewel. Honoring a warranty of this type internationally can be expensive, in fact ruinous, if the tools are routinely defective, but a responsible retailer selling quality tools should be able to handle it. We believe it’s only fair that most of the expense of making good on the warranty be borne by the retailer, not the customer, a principle that has been called having “skin in the game.” What do you think?

At C&S Tools we offer a full warranty on materials and labor. If the tool is either defective in materials or workmanship, or not what we represented it to be, and on condition that (i) your expectations for hand-forged tools are realistic (perfection is unattainable); and (ii) you have done your job correctly and not abused the tool or failed to maintain it properly, we will either replace or repair the tool or refund the purchase price. If indeed we or the tool are at fault, we will also refund all pre-approved shipping costs. That’s truly the best international warranty in the business, one we put in writing in all our invoices without weasel words, and one we honor.

If you have a problem, simply let us know by email and we will respond. You will not be told to “take a number” from a dispenser that looks like a hand grenade. You will not be ignored.

Free, Useful Information Without Strings

Knowledge is power.

There’s a lot written in plain, mystery-free language in the many pages in this blog to help you learn what you need to know to make wise decisions about Japanese handtools. We encourage you to plug-in to this power; Batteries are not required.

While we’re on the subject of cords, you may have noticed that this blog is unusual in that it has no advertising, and no sponsors, not even promos for video games, home-security systems, or pickle enhancement cream. It produces zero income by itself. Foolish as it seems, we have no SEO strategy. Patreon is a brand of non-stick frying pan, right?

Please also notice the lack of banners and links to e-commerce pages; We most definitely do not have an “internet platform.” We only sell tools to people who want them enough to directly ask for them instead of just clicking virtual buttons because keeping product in-stock is not easy with the dramatic decrease in active blacksmiths nowadays.

If you ask a question, make a comment, or purchase something from us we will never share or sell your information. We hate data miners for they are greasy sneak-thieves.

The Three Options

Let us next directly address the title of this article.

There is an ancient, venerable saying, a version of which goes like this: “You have three options: (1) Beautiful Appearance; (2) High Quality (cutting performance in the case of chisels, planes and saws); and (3) Low Cost. Choose any two.”

The corollary to this saying goes something like this:

- A wise man may obtain a maximum of two of these three options;

- Many do well to get one out of three;

- The careless often get none out of three;

- The fool believes he got them all.

What are Gentle Reader’ priorities with regard to these three options ?

C&S Tools’ Priorities

Being deeply aware of the importance of these three options in the physical world, we have established priorities and strictly follow measurable standards and specifications for our products, as follows.

We place highest priority on highest-quality materials, skilled hand-forging, and rigorous heat-treatment to ensure the ideal crystalline structures are formed in the blades of our cutting tools and maximum possible performance is always achieved because they are working tools for professional woodworkers. This is absolute.

Reasonable price is a close second priority because they are working tools for professional woodworkers.

Appearance is third because they are working tools for professional woodworkers, not “safe queens” for collectors.

Perfection in anything is unattainable, but the pursuit of it is extremely expensive, I assure you. Indeed, beautiful appearance in a hand-forged tools is an attribute your humble servant dearly loves and has spent oodles of cashy money over the years pursuing, but it is a difficult thing to achieve, requiring a well-polished eye, advanced skills, and many hours of expensive handwork with scrapers, files and sandpaper, efforts that contribute nothing to a working tool’s performance and are therefore not critical to the professional woodworker, so we assigned it lowest priority.

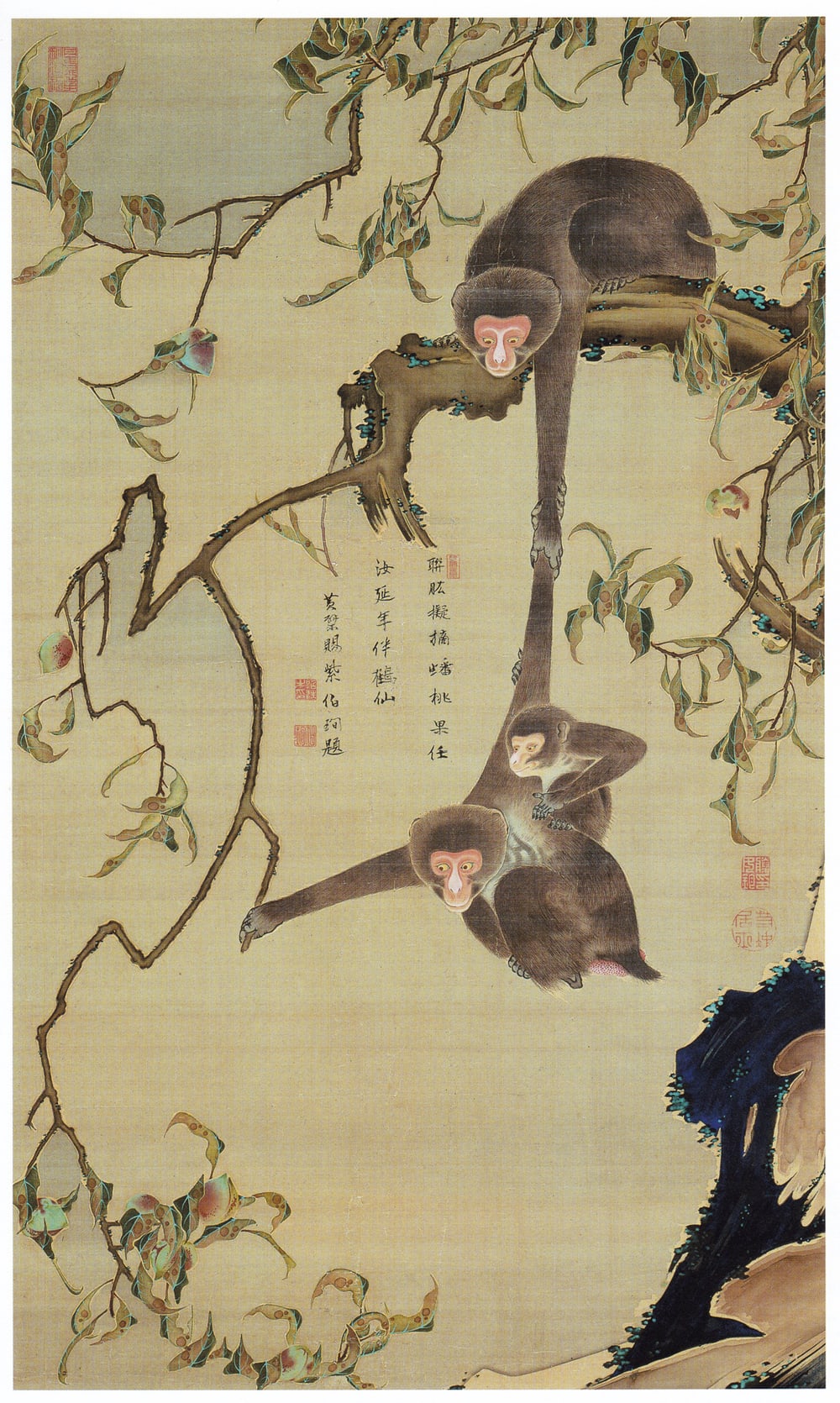

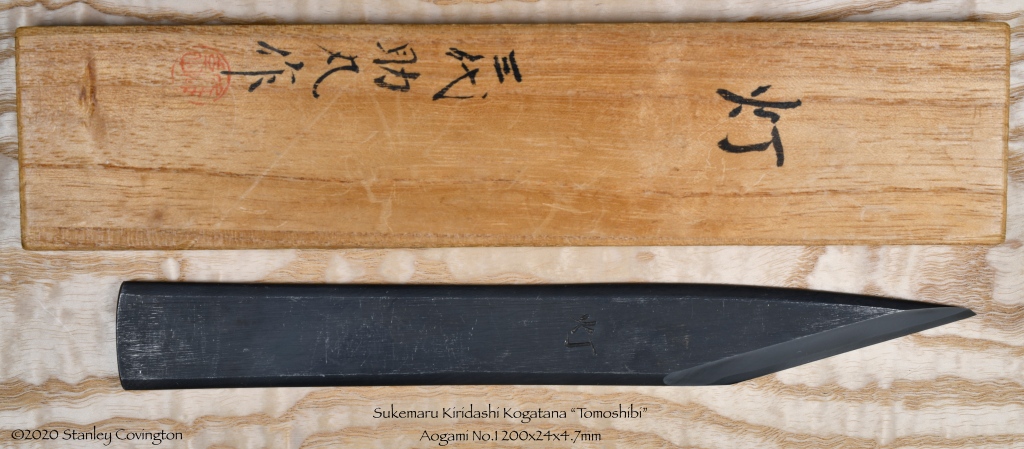

To achieve both the target appearance and price, our blacksmiths shape with fire, hammer and grinder and finish with sanders, not scrapers or files. The results look pretty good, but are not up to Ichihiro’s standards of beauty (the chisel at the top of this page is an authentic atsunomi by Ichihiro). Fortunately, the prices are not up to Ichihiro’s standards either, thank goodness.

The wise man will say “two outa three ain’t bad,” but what about the fool?

Let’s next examine a real-world example of someone who thought they were oh so frikin clever.

A Real-world Example

An extremely famous foreign luxury automobile manufacturer built a maintenance facility in Japan 30+ years ago, which they subsequently converted to another, lighter usage.

This building was constructed under the company’s immovable corporate procurement policy of always putting construction projects out to competitive bid, and after bids are formally submitted, but before awarding a contract, relentlessly playing bidder against bidder in negotiations to reduce their bid prices, sometimes even rebidding the project online, effectively negating the concept of competitive bidding, a practice that is patently unfair in the private sector and absolutely illegal in public bidding. As a direct result of this policy, and because producing a bid in Japan can easily cost a bidder $100,000, quality general contractors in Japan now absolutely refuse to bid this company’s projects, leaving only small, 3rd rate contractors with poor capabilities and minimal quality control left as potential bidders.

This automotive company later decided to remodel and modernize their old building, changes placing additional loads on the structural system. Since the building was supposedly originally designed to handle the heavy loads of many moving vehicles on all floors in an area with weak soils and high earthquake forces, it should have had plenty of structural strength in reserve, at least enough to accommodate these minor additional loads, right? Shockingly, a structural check revealed that the building not only had zero reserve strength, but that the original structural design (performed by another lowest bidder) was clearly inadequate. Consequently, what should have been a strong building was actually shockingly weak.

Foolish policies established in Europe to unfairly reduce costs forced the company in Japan to hire an incompetent architect and engineer, and a careless contractor 30+ years ago, one with a poor reputation even now, one focused like a laser on getting the job done and receiving final payment with the least possible expenditure of manpower, consequences past the statute of limitations be damned.

The result? Not only were the company’s minor renovation plans frustrated, but the safety of their building in earthquake-prone Japan was revealed to be insufficient, necessitating an expensive and time-consuming structural retrofit ultimately wasting time and money all while placing employees and customers at risk for 30+ years. Talk about unintended consequences.

When originally completed, the building looked beautiful, it seemed high-quality, and the design/construction cost was extremely low, easily satisfying all three of the “options” listed above, or so it seemed.

The moral of the story can be found in the answer to this question: “Was the building’s owner the wise man, the lucky man, or the fool?”

What are your priorities?

YMHOS

If you have questions or would like to learn more about our tools, please click the “Pricelist” link here or at the top of the page and use the “Contact Us” form located immediately below.

Please share your insights and comments with everyone in the form located further below labeled “Leave a Reply.” We aren’t evil Google, fascist facebook, or thuggish Twitter and so won’t sell, share, or profitably “misplace” your information. If I lie, may there be no graceful storks in my life, only Chinese excreta.

Leave a comment