Quality is not an act, it is a habit.

Aristotle, 384–322 BC

In this article your humble servant will introduce a standard woodworking tool which I believe to be unique to Japan, although I have no doubt individual craftsmen around the world have produced versions of it for their own use for thousands of years.

I will explain the jobs this tool is used for, how it is used, how to fettle it, and how to sharpen it. I will also share some first-hand business insight regarding why Japanese women make this tool essential to the joiner in both performing traditional joinery in Japan, as well as the sometimes challenging task of getting paid for his work.

Mr. Spock will also make a brief contribution to the discussion.

Definition & Pronunciation

The Sokozarai Nomi (pronounced Soh/koh/zah/rahi noh/me and written 底浚い鑿 ) translates to “bottom-cleaning chisel.”

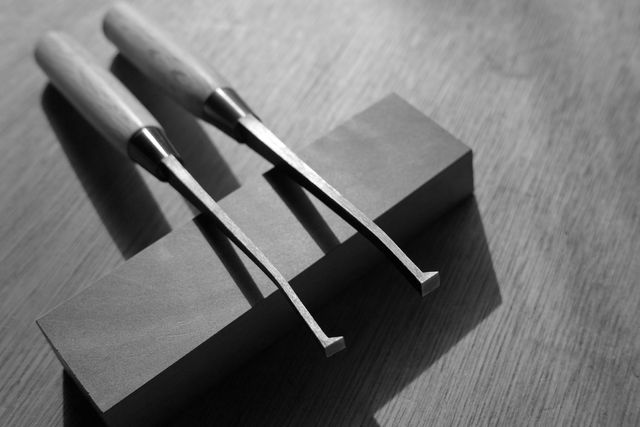

It is a simple tool consisting of a differentially-hardened steel shaft, with a small, short, sharp foot formed at the end, attached via a tang to a wooden handle, and secured by a conical ferrule.

The Sokozarai chisel is one of three specialized chisels used specifically for joinery work. Cabinetmakers and furniture makers use it too. Two other specialty joiner chisels are the “Mori Nomi,” which translates to “harpoon chisel,” and “Kama nomi,” which translates to “sickle chisel.” Perhaps we will discuss these in a future article.

A larger version of the sokozarai chisel is used for cleaning the bottom of the larger mortises commonly cut in timber frames.

The Role of the Sokozarai Chisel

The sokozarai chisel is used for two purposes. The first is loosening and removing chips from inside mortises. One simply hooks the offending waste with the chisel’s toe and flips it out.

The second role of the sokozarai chisel is to flatten and even plane mortise bottoms. When set up correctly, it will cut shavings from the bottom of mortises cut in softwood planing them flat and clean.

Indeed, in advanced joinery work, a skillful joiner will plan and execute his joints such that the material left remaining at the bottom of a mortise cut into a stile intended to receive the tenon from a rail is less than 1mm thick, thin enough to allow light to pass through. The ability to routinely cut joints like this, without cutting all the way through, is a mandatory skill of the professional joiner.

I suspect that about now Gentle Reader is forming his elegant eyebrow into an artistic and skeptical arc as he ponders why one would go to the trouble of making clean and pretty the bottom of a hole upon which no one will ever gaze, leaving a paper-thin wall of uniform thickness at the bottom admitting light into a space no one will ever see. Can there possibly be method to this madness? Welcome to traditional Japanese joinery.

Consider that a rough, bumpy floor in a mortise prevents the tenon from seating the last few millimeters, but by planing it flat with a sokozarai chisel, those last few millimeters can be converted to useful space to house maximum-length tenons ensuring maximum resistance to withdrawal and bending forces resulting in strong, slender but durable joinery without adding extra weight. This is a big deal in the case of the slim, flexible frame members found in operable traditional Japanese joinery such as shoji, itado and tsuitate screens, joinery that must satisfy the severe eye and meet the high standards of fit and finish expected by many Japanese women, the most unforgiving consumers in the world.

I don’t know when this detail entered common use, but as Gentle Reader is no doubt aware, the older and more common type of mortise and tenon joint found in joinery worldwide is the through single or double tenon with the tenon’s end exposed at the rail where it is often wedged, a technique that is undoubtedly stronger.

On the other hand, the fully-housed tenon made easier to fabricate using the sokozarai chisel has two advantages over its older, less-refined brother the through-wedged tenon. First, it simply looks better and more elegant when new, and is therefore better able to survive the strict final inspection by the lady of the house thereby more reliably earning the reward of final payment. Hallelujah, pass the bottle brother!

Second, it simply looks better to the eye and feels better in the hand as time goes by because, as the stile shrinks during drier months, the once flush end of the through-tenon won’t project past the surface of the stile creating an unslightly, uncomfortable bump, and during the wetter months it won’t recede back into the mortise leaving an indentation in the stile and an uneven appearance.

These details are not based on esoteric imaginings about quality, but are make or break business decisions essential to avoiding complaints from the same unforgiving Japanese women. And of course, in a country where advertising and representations are routinely and intentionally false (sad but true), word of mouth among sharp-eyed quick-tongued women is critical to a craftsman’s success. Please note that I say this as someone who has has been married to a Japanese woman for 45 years, has lived and worked in Japan for over 32 years, and during those years has had plenty of direct commercial experience working with Japanese women as both customers and team members.

Next time we are sharing a cup of hot cocoa around the evening fire, remind me to tell you the story about two stressful days spent inspecting Thassos marble slabs for a new building’s lobby walls in the company of three Japanese women: an Architect, a Quantity Surveyor, and a Project Manager. All the story lacks is a Rabbi and a Priest to make a gut-splitting joke (ツ)。

Using the Sokozarai Chisel

To use the Sokozarai chisel, and assuming you are right-handed, hold the handle in a fist in your right hand with the blade projecting from the bottom of the fist. Lay the back of the fingers of your left hand on top of and crosswise to the long direction of the mortise. Insert the blade of the chisel into the previously cut mortise hole and press the back of the blade’s neck (opposite the cutting edge of the foot) against the outside edge of your forefinger. Then pinch the blade’s neck between your thumb and forefinger. This is the grip.

To remove loose waste, insert the sokozarai chisel into the mortise hole and move it around gathering chips on the chisel’s toe. Then pull the chisel up and out of the mortise quickly to pop chips out.

To cut loose chips still attached in the mortise hole, press the chisel’s foot to the bottom, move it forward until it snags on irregularities, then rotate the handle towards your body using the forefinger of your left hand as a fulcrum to lever waste out.

To shave the bottom, simply move both hands forward with the bottom of the foot parallel with the intended bottom of the mortise. Developing a sense of the chisel’s action will take practice. Shining a flashlight into the mortise frequently at first will help develop these senses.

To check the depth of the mortise, a specialist kamakebiki, essentially a small router plane, is ideal. But you can make a simple depth gauge by sharpening the edges of the head of a nail or drywall screw, driving or screwing it into a small block of wood, then cutting off and filing the point to avoid ouchies. Using this, you will be able to detect bumps and irregularities remaining on the bottom. Indeed, it too can be used to shave the bottom, but it won’t clean all the way into corners unless you grind the head square or rectangular.

For advanced work, make a slightly undersized test stub tenon with shoulders from hardwood the depth of the finished mortise, and anoint the end with cheap dark lipstick or Vaseline with black oil pigment mixed in. High spots remaining at the bottom of the mortise will be highlighted. With practice, you won’t need this test tenon, but you will still definitely need a sokozarai that is sharp enough to plane the bottom.

Next, let’s consider how to prepare a new sokozarai chisel.

Fettling the Sokozarai Chisel

Unlike most other Japanese chisels, the Sokozari chisel is not laminated construction, but is formed of one piece of differentially-hardened high-carbon steel. Differentially-hardened in this case means that the foot and lower 1/4 of the leg’s length are hardest, becoming progressively softer going up the leg until it is dead soft at the tang. This means the cutting blade, (what your humble servant calls the “foot”) of this chisel will become sharp and stay sharp, but the neck is left softer so it will not snap off, and can even be bent a little to adjust the angle of the foot if necessary.

Low-quality sokozarai have both soft shafts and feet.

Flatten and Polish the Foot’s Bottom

The bottom of the foot needs to be flat and polished, but because of this surface’s narrow width and short length, it can be challenging to accomplish without rounding it over or skewing it.

It often helps to grind a hollow into the foot’s bottom the thickness of a nat’s eyebrow to help speed up the flattening and polishing process. If you use a grinder, be very careful to avoid overheating. It should take no more than one or two brief touches to the wheel.

When flattening and polishing the foot’s bottom surface on diamond plates and stones, it also helps to make a guide block. Cut a slot in the side of a small block of hardwood to house the bent shaft with the bottom of the foot located flush with the block’s bottom surface. Lock the shaft into the guide block with a wedge or a clamp to stabilize it.

The jig in the photos above was made by a Most Beloved Customer who does exceptional high-quality joinery work.

An alternate sharpening jig can made by cutting a crosswise groove, similar to the one shown in the photo below, into the top surface of a stick of scrap wood, perhaps 50mm wide, 200mm long and 20mm thick. The bottom surface of the foot should be almost, but not quite flush with the stick’s edge, projecting the thickness of a piece of paper. Secure this jig to your workbench with a clamp or in a vise, press down on the blade with one hand, and move a sharpening stone along the side of the jig over the foot.

This guide block rides directly on the stone as you flatten and polish the foot’s bottom. Don’t let the foot’s bottom get skewed or rounded over. Work slowly and check constantly. This is a one-time operation.

Once the bottom is flat and polished, you should only need to polish the bottom of the foot on your finishing stone.

Adjust and Polish the Cutting Edge’s Bevel

The bottom of the foot is now flat and pretty, but the angle of the cutting edge is usually still far too steep, and the bevel’s surface is rough. This must be corrected.

Modify the cutting edge’s angle by grinding the bevel on a diamond plate. The final angle you chose for the cutting edge will depend on your preferences and the wood you will be cutting. Steeper angles are more durable. Shallower angles cut better, but dull quicker. 20~24 degrees is usually OK. When I was a young man, I knew professionals who took the bevel angle down to 15 degrees.

You may want to make another narrower guide-block clamping 90 degrees across the the shaft to help hold/stabilize the blade during this operation. When you have adjusted the angle to where you want it to be, then polish it on your sharpening stones. Be careful to avoid skewing it or rounding it over. You want sharp, clean corners.

To routinely sharpen/polish the bevel, hold the chisel in one hand with the bevel face-down on the long side of your sharpening stone. While stabilizing the blade and applying pressure on the bottom of the foot with a fingertip, move the sokozarai chisel back and forth in small strokes being careful to avoid rocking it and rounding it over.

Adjust the Foot’s Length

This step is unnecessary for most applications, but I will touch on it just to be thorough.

The length of the foot is fine as-is for most furniture mortises, but for very tiny mortises as in screens, light fixtures, and small casework, the foot may need to be made shorter. It is not unusual for a tategushi or sashimonoshi to own multiple sokozarai nomi with feet and shafts of different widths and lengths and bevel angles to clean the mortises he makes the most.

Please note that the mortise holes for kumiko members installed in shoji screen and most other types of latticework are shallow and do not require the strength of long tenons, so the mortises are usually cut using mori nomi (harpoon chisels) with a hook on the end to pull out waste quickly, and the bottoms are left rougher.

Conclusion

Beloved Customers that have purchased our chisels, and diligent Gentle Readers that have read this blog, are aware that your humble servant insists our chisels not be used to scrape or lever waste out of joints. The reasons for this are my desire for Beloved Customer’s most excellent chisels to remain as sharp as possible as long as possible, and to avoid chipping the cutting edge. They are, after all, refined cutting tools with sensitive feelings, neither thuggish prybars nor pot-metal screwdrivers.

The Sokozarai chisel was invented specifically as a partner to chisels used for cutting the clean mortises essential to Japanese joinery, and to protect the super-sharp cutting edges of those chisels from damage resulting from barbaric treatment. I encourage you to level-up your joinery skills by procuring and using one. You will be glad you did.

And so I wave farewell until the evening we share a cup of hot cocoa around the irori fire. In the meantime, I am humbly grateful for the honor to remain,

YMHOS

If you have questions or would like to learn more about our tools, please click the “Pricelist” link here or at the top of the page and use the “Contact Us” form located immediately below.

Please share your insights and comments with everyone by using the form located further below labeled “Leave a Reply.” We aren’t evil Google, fascist facebook, or thuggish Twitter and so won’t sell, share, or profitably “misplace” your information. If I lie may my sokozarai chisels get athletes feet!

Links to Other Posts in this Series

- The Varieties of Japanese Chisels Part 1 – The Main Categories

- The Varieties of Japanese Chisels Part 2 – The Mentori Oiirenomi (面取追入鑿)

- The Varieties of Japanese Chisels Part 3 – The Shinogi Oiirenomi (鎬追入鑿)

- The Varieties of Japanese Chisels Part 4 – Kakuuchi Oiirenomi (角打追入鑿)

- The Varieties of Japanese Chisels Part 5 – High-Speed Steel Oiirenomi (HSS 追入鑿)

- The Varieties of Japanese Chisels Part 6 – The Mortise Chisel (Mukomachi Nomi 向待鑿)

- The Varieties of Japanese Chisels Part 7 – The Nihon Mukomachi Nomi (二本向待鑿)

- The Varieties of Japanese Chisels Part 8 – The Atsunomi (厚鑿)

- The Varieties of Japanese Chisels Part 9 – The Uchimaru Nomi Gouge (内丸鑿)

- The Varieties of Japanese Chisels Part 10 – The Sotomaru Nomi Incannel Gouge (外丸鑿)

- The Varieties of Japanese Chisels Part 11 – The Tsuba Nomi Guard Chisel (鍔鑿)

- The Varieties of Japanese Chisels Part 12 – The Usunomi Paring Chisel (薄鑿)

- The Varieties of Japanese Chisels Part 13 – The Shinogi Usunomi 鎬薄鑿 Paring Chisel

- The Varieties of Japanese Chisels Part 14 – Kote Nomi (鏝鑿Trowel Chisel)

- The Varieties of Japanese Chisels Part 15 – Ootsuki Nomi (大突き鑿)

- The Varieties of Japanese Chisels Part 16 – HSS Atsunomi

- The Varieties of Japanese Chisels Part 17 – The Sokozarai Chisel

- The Varieties of Japanese Chisels Part 18 – The Hantataki Chisel

A timely post for me. I have a relatively new sokozarai but had not sharpened it. Today I made a jig like the one in the photos and it worked great for flattening and polishing the sole of the foot. Thanks also for the tip about adjusting and sharpening the bevel. I used a file to slowly and carefully adjust the bevel, and then sharpened and polished on stones. I haven’t used it yet so I don’t know if I got it right but it is good to know the process.

LikeLike