Behold, I have created the smith that bloweth the coals in the fire, and that bringeth forth an instrument for his work.

Isaiah 54:16 KJV

In the previous post we looked at some of the supernatural aspects of making and forging steel. In this post we will examine some alchemical aspects of woodworking blades, in the particular the iron and steel used to make them and the related chemistry of sharpness and sharpening.

This post could be very technical, but your humble servant has simplified the description of chemical processes to make it easier for the non-technical Gentle Reader to follow. Please bear with me.

The Alchemy of Mutating Iron to Steel

When carbon is combined with iron in the right proportion, steel is formed. This mutation is easily accomplished nowadays, but for most of human history it was a fiendishly difficult, chancy, expensive process. No wonder those who could accomplish the deed were attributed with magical powers.

But just mixing chemicals does not yield a useful cutting tool. No, the blacksmith must make the steel hard enough to hold a cutting edge, but tough enough to endure actual work. The catalyst for this mutation is heat. The ability to create a fire hot enough to melt iron was, until fairly recently on the scale of human history, the biggest hurdle to producing quality steel consistently.

If steel is heated to within a specific range of temperatures (difficult to measure by eye) and then suddenly cooled, crystalline structures containing small, very hard and relatively brittle crystals called carbides form within a softer matrix of iron. These hard carbides supported in this rigid crystalline structure are what do the serious job of cutting, not the softer matrix.

At the extreme cutting edge, this structure might be compared to a modern circular saw blade comprised of a relatively soft body to which is attached very hard tungsten carbide cutting tips.

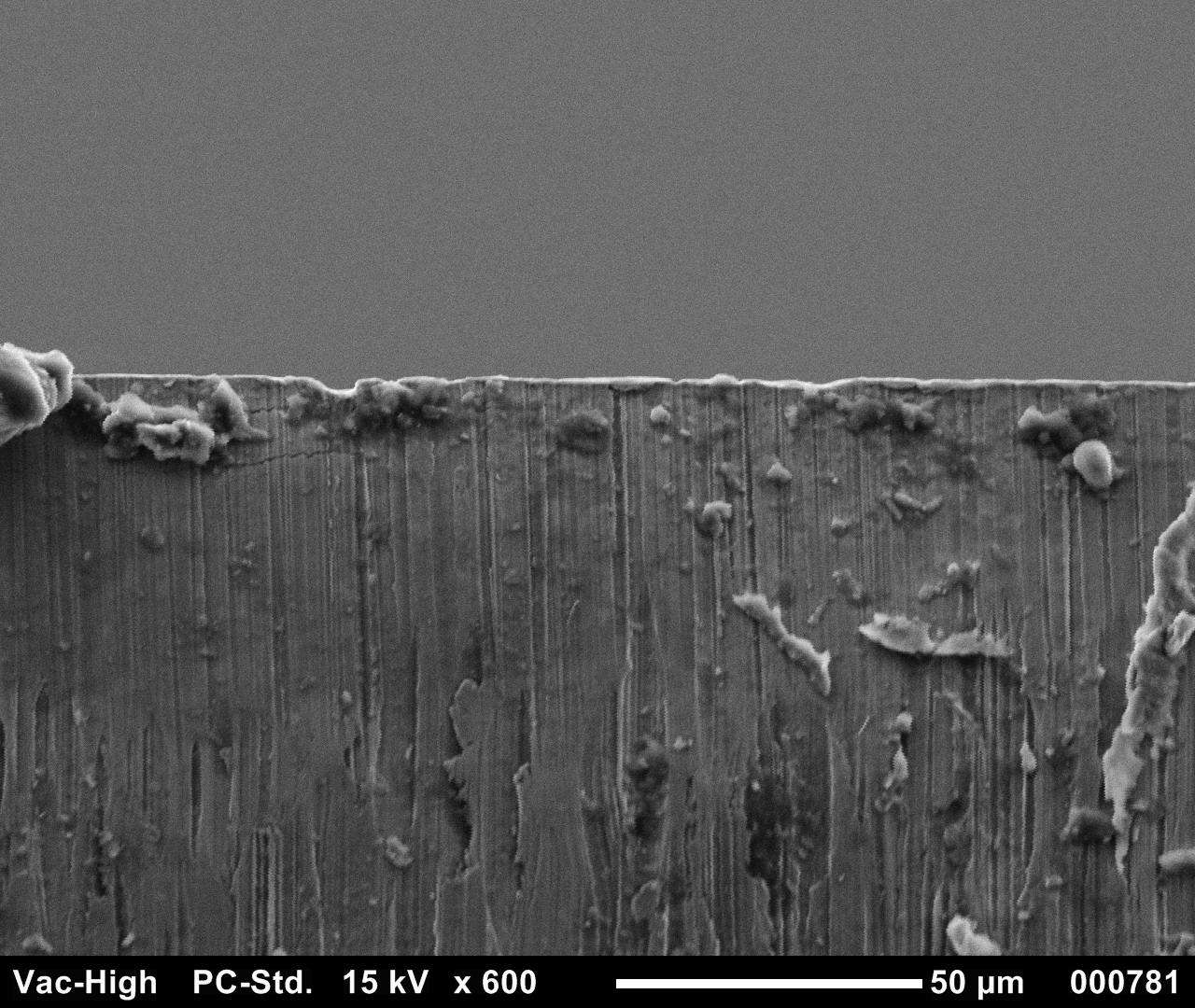

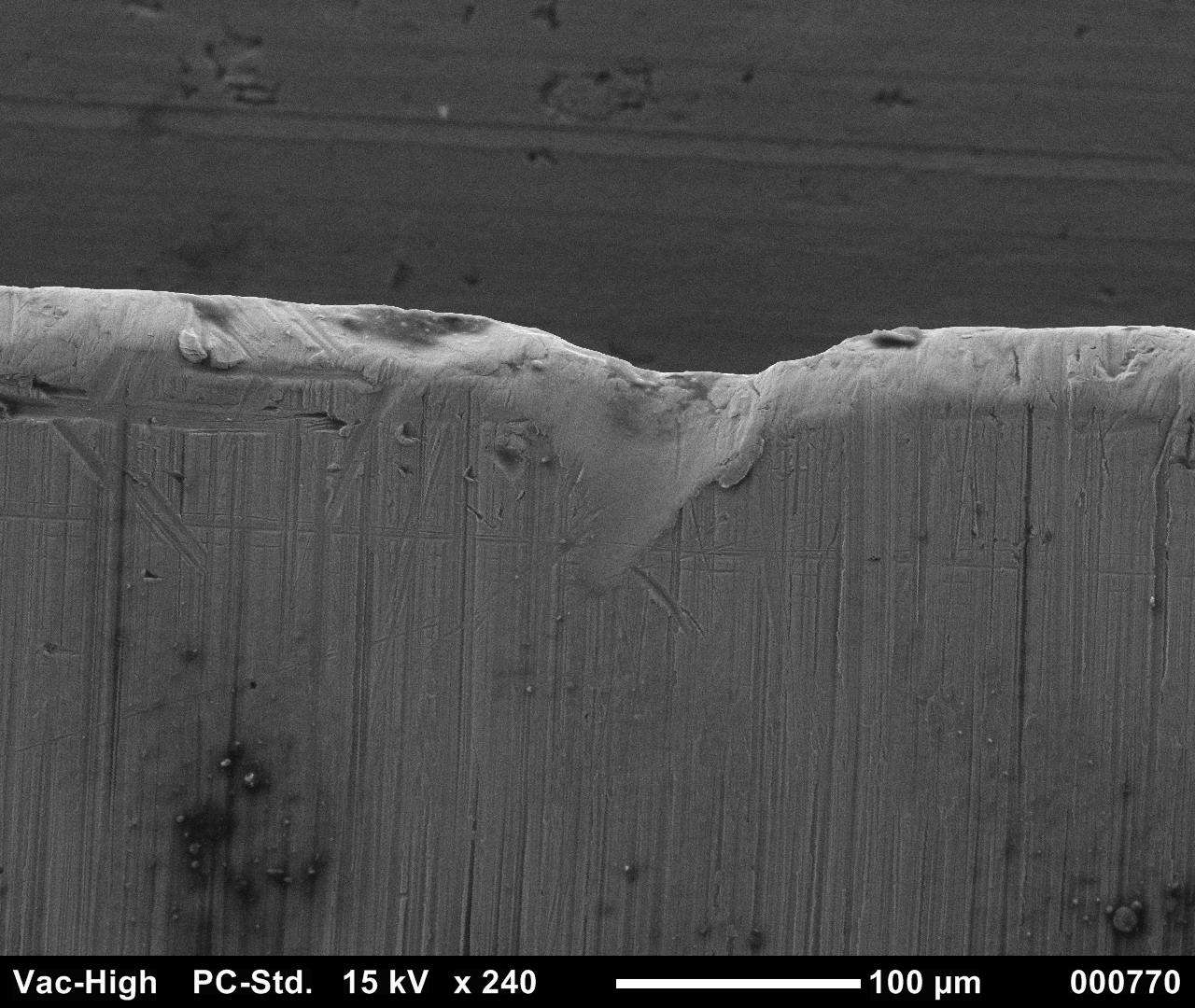

A steel blade dulls when the crystalline structure either shatters, or the pressure and friction of cutting wears away or cracks the softer supporting matrix, allowing the carbides to be torn from the matrix leaving behind gaps of soft, blunt metal. The larger the carbide clumps are and the greater the distance between them, the more easily they are shattered and torn away, and the duller a blade becomes with each crystal’s failure.

In a low-quality blade, and given the same amount of carbon in a fixed volume of steel, the crystals will form into relatively large and isolated clumps separated by wide rivers and lakes of softer metal, as seen from the viewpoint of a carbide. The steel will crack along these weaker pathways when stressed, and when cutting, the softer material in these lakes and rivers will erode first, leaving the desireable carbide clumps unsupported and more vulnerable to failure.

In a high-quality steel blade, by comparison, and given the same amount of carbon in a fixed volume of steel, the crystalline clumps are comparatively smaller and distributed more evenly throughout the matrix making it more resistant to erosion, and the carbide crystals more resistant to damage. Such steel is called “fine grained,” and has been highly prized since ancient times for its relative toughness and ability to become very sharp and stay sharp for a long time. This is the steel preferred by woodworking professionals in Japan and is the only kind found in our tools. Without exception.

Sadly, this crystalline structure is not visible to the naked eye, and anyone who says differently is trying to sell Beloved Customer something brown and smelly, probably with a side dish of flies.

Impurities and Alloys

Other than excellent and abundant water, endless forests, mountains overgrown with wonderful trees, and diligent people, the islands of Japan are poor in most of the natural resources critical to industrialization, including iron ore, coal, and petroleum. Prior to the mass importation of such resources after 1854, the best source of iron in Japan had been black sand (satetsu 砂鉄) found in rivers. The article at the following link details some of these traditional Japanese production methods: A Story of a Few Steels

Regardless of their source, all iron ores naturally contain impurities such as phosphorus, sulfur, or silicon to one degree or another. When these impurities exceed acceptable limits, they can weaken the steel, make it brittle or tend to warp badly, or make heat treating results inconsistent. They are often expensive to remove.

There are three approaches commonly used to minimize the negative effects of these difficult-to-remove impurities. The first is simple avoidance of the problem by employing iron ore and scrap metal free of excess amounts of these contaminants. Such ore and scrap are available, but they are not found everywhere and are relatively expensive. For centuries, the purest iron ore has been mined in Sweden.

The second approach is to add purer iron or carefully sorted and tested scrap steel to the melting pot thereby reducing the percentages of the harmful contaminants, a technique called “ solution by dilution.”

The third fix is to add chemicals such as chrome, molybdenum, nickel, tungsten, vanadium and even lead to the pot forming steel “alloys” to help overcome the detrimental effects of natural impurities, specifically those related to brittleness, warping and unpredictable heat treatment. Some additives will make the steel more resistant to abrasion and corrosion, or even easier to cast, drop-forge, or machine.

Some steel alloys have serious advantages over plain high-carbon steel in mass-production, for example reducing material costs by allowing the use of cheaper lower-grade iron ore and scrap metal, or improved working and heat-treating characteristics making it possible to achieve higher productivity with fewer rejects even when worked by low-skill workers.

But the addition of these chemicals is not all blue bunnies and fairy farts because edged tools made from high-alloy steels typically have some disadvantages too. For instance, additives like chrome, nickel, molybdenum, vanadium and especially tungsten are costly. And due to the crystalline structure that develops in many high-alloy steels, products simply cannot be made as sharp as plain high-carbon steel, and are more difficult and time-consuming to sharpen by hand.

Some manufacturers cite the higher costs of high-alloy steels to justify higher prices for their products. However, what they never say out-loud is that labor costs are much much less when using high-alloy steel because skilled workers are not necessary. And because high-alloy steels produce fewer rejects, quality control is easier, overall productivity is higher, warranty problems are fewer, and profitability is increased. Indeed, without high-alloy steels, manufacturers would need to train and hire actual skilled workers and professionals instead of uneducated seasonal workers thereby destroying the Wally World mass-production model that is the foundation of modern society. Egads! Walmart’s shelves would be bare!

Our blacksmiths are not part of the Wally World production model, but make only professional-grade tools for craftsmen that value ease of sharpening, edge retention, and cutting performance above corporate profits. They charge more for plain high-carbon steel blades than for high-alloy steel products because labor and reject costs are higher.

So if a manufacturer brags about the excellence of the high-alloy steels they are using, rest assured increased profits are their motivation, not improved cutting performance. Caveat emptor, old son.

Japanese Steels

The best plane and chisel blades are made from plain, high-purity, high-carbon steel. In Japan, the very best such steel is made by Hitachi Metals mostly using Swedish pig iron and carefully tested industrial scrap (vs used rebar and old car bumpers), and is designated Shirogamiko No.1 (白紙鋼 1 号 White-label steel No. 1). They also make a steel designated Shirogami No.2 steel containing less carbon. Another excellent steel for plane and chisel blades is designated Aogamiko No.1 steel (青紙鋼 Blue-label steel).

Aogami steel, like Shirogami steel, is made from extremely pure iron, but a bit of chrome and tungsten are added to make Aogami steel easier to heat treat with less warping. Aogami can be made very sharp, but it is not quite as easy or pleasant to sharpen as Shirogami. Some of the plain high-carbon Swedish steels are also excellent.

If worked expertly, either of these steels consistently produce the highest quality “fine-grained” steel blades.

Let’s compare the sharpening characteristics of these two steels. To begin with Shirogami steel is easy, indeed pleasant, to sharpen. It rides stones nicely and abrades quickly in a controlled manner.

Aogami steel, by comparison, is neither difficult nor unpleasant to sharpen, but it is different from Shirogami steel in subtle ways. It takes a few more strokes to sharpen, and feels “stickier” on the stones, but it will still produce fine-grain steel blades and performs well.

Inexperienced people lacking advanced sharpening skills typically can’t tell the difference between blades made from Shirogami, Aogami or Swedish steel and steels of lesser quality. But due to the difficulty of forging and heat treating Shirogami or other plain high-carbon steels, a blacksmith that routinely uses them will simply be more skilled and have better QC procedures than those whose skills limit them to using only less-sensitive high-alloy steels.

Professional Japanese woodworkers insist on chisel blades made from Shirogami No.1 steel. Some prefer Aogami No.1 for plane blades believing the edge holds up a bit better. At C&S Tools our plane blacksmith prefers to use Aogami because it is easier to work and more productive (especially in the case of carving chisels), but for a little extra they are happy to forge blades from Shirogami Steel.

I own and use Japanese planes made from Shirogami, Aogami, Aogami Super, Swedish steel, and a British steel called “Inukubi,” which translates to “dog neck,” a commercial steel imported to Japan from England (Andrews Steel) in the late 1800’s. Of these, Shirogami No.1 steel is my favorite. It’s a matter of personal taste.

Beware of a plane or chisel blacksmith that refuses to use plain high-carbon steel and tries to charge you more for blades made from Aogami or Aogami Super steel.

The Challenges of Working Plain High-Carbon Steel

What makes plain high-carbon steel so difficult to work, you ask? Your humble servant has never even forged a check much less a tool blade, but I will share with you what the blacksmiths I use and swordsmiths I know have told me in response to this question.

First, plain high-carbon steel is much more difficult to successfully heat treat because the range of allowable temperatures for forging and heat-treating is narrow. Heat it too hot and it will “burn” and be ruined. Quench it at too high or too low a temperature and it will not achieve the desired crystalline structure and/or hardness. Miss the appropriate range of temperatures and the blade may even crack, ruining it. Yikes! Please see the numbers and photos in the article linked to above.

Second, even if the temperatures are nuts-on, plain high-carbon steel has a nasty habit of warping and cracking during heat treating resulting in more rejects than alloy steels with additives such as chrome, tungsten or molybdenum. Strange as it may seem, when the crystalline structures that make steel useful form during quenching, they increase the blade’s volume. This change produces differential expansion causing the metal to warp, a troublesome characteristic that can be more or less controlled, or at least compensated for, by a skillful blacksmith, but it takes real skill, extra work, and a bit of luck. Not just any old Barney can do it consistently, so when working plain high-carbon steel, a blacksmith needs to know his stuff and pay close attention.

Other than wastage due to rejects, it doesn’t cost more to forge and heat-treat a blade made from plain high-carbon steel, but it takes serious skills and dedication to quality control to make a living working it for 5+ decades.

Let me give you an example of skill and experience as it relates to warpage management of plain high-carbon steel.

The photo below is of a swordsmith the instant before he quenches a glowing hot sword blade made of tamahagane, a traditional type of plain high-carbon steel made from iron sand, in a water trough. Notice the condition of his smithy: he is working in the middle of the night, the time when the best magicians and alchemists have always done the most difficult jobs because temperatures are easier to judge without inconsistent sunlight confusing things. His posture and facial expression are tense because he is about to roll the bones and, in the blink of an eye, either succeed in the most risky part of making a sword, or fail wasting weeks or months of work and thousands of dollars worth of materials. Notice how straight the glowing blade is before the plunge.

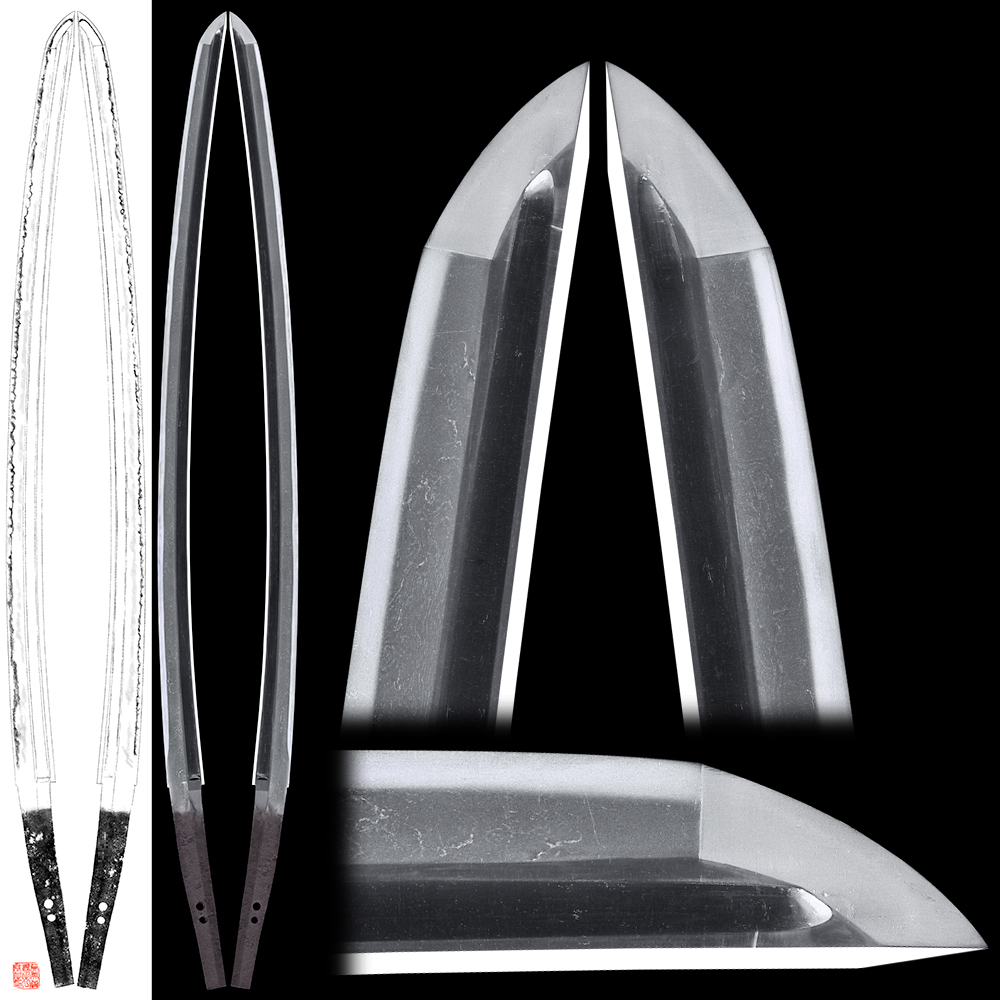

Note that the quantity of crystalline carbides formed in a Japanese sword during the quench is greatest nearest the hard cutting edge, and cause that area of the blade to expand and warp the most. The swordsmith therefore forges the blade straight before quenching it in expectation of it warping to the intended curvature when the crystalline structures at the cutting edge form, as seen in the photo below. This curvature is an intentional design feature that takes years of experience to achieve in a controlled manner.

If the swordsmith intended to make a straight sword blade, he would have a forged a reverse curvature into the blade to compensate for the warpage that occurs during quenching. Plane and chisel blades exhibit similar but less dramatic behavior due in part to the moderating effects of the low/no-carbon lamination.

The thinner the piece of steel being heat-treated, the more unpredictable the warpage developed and more likely the blade will be to develop fatal cracks. Within limits, simple warpage can be corrected to a limited degree in thin blades during the first few seconds after quenching and/or tempering by bending and/or twisting the blade while it is still hot and malleable. These techniques do not work well in the case of thicker plane and chisel blades, however, so experienced blacksmiths don’t rely solely on corrective measures but anticipate warpage beforehand and create a curve or twist in the opposite direction when forging the blade to compensate. This takes skill and experience, and even then, some rejects are unavoidable.

Chemical alloys like chrome, molybdenum, and tungsten greatly reduce warping and the risk of cracking, so their benefits are huge.

None of this is mystical, but tools made from plain high-carbon steels such as Shirogami steel require more skill and experience than those possessed by factory workers, much less Chinese peasants, so mass-production is nearly impossible, labor costs are higher, profit margins are smaller, and advertising budgets are non-existent. No wonder such tools get little attention from the shills in the woodworking press.

While modern chemistry has unveiled the mystery of steel, it has only been during the last 70 years or so that metallurgical techniques were developed making it possible to understand the Mystery of Steel, and the tools to scientifically control the Alchemy of Steel are even younger.

The manufacture and working of steel are still magical processes that are the foundation of modern civilization. Be not deceived: while computer nerds, ijits with MBAs, and governments grifters take all the credit, without the alchemy of steel and the skill to use it, human life on the mudball we call home would be short and brutal.

If you have good sharpening skills but haven’t yet tried chisel or plane blades made from Shirogami, Aogami or Asaab K-120 Swedish steel, you’re missing a treat.

In the next article in this magical series we will examine the genius of the soft iron component found in quality Japanese woodworking blades. Whether cat, bat or owl, please explain the details to your familiar to prepare them for the excitement to come!

YMHOS

If you have questions or would like to learn more about our tools, please click the “Pricelist” link here or at the top of the page and use the “Contact Us” form located immediately below.

Please share your insights and comments with everyone in the form located further below labeled “Leave a Reply.” We aren’t evil Google, fascist facebook, or thuggish Twitter and so won’t sell, share, or profitably “misplace” your information. If I lie may everything I eat taste like mud.

Links to Other Posts in the “Sharpening” Series

- Sharpening Japanese Woodworking Tools Part 1

- Sharpening Part 2 – The Journey

- Sharpening Part 3 – Philosophy

- Sharpening Part 4 – ‘Nando and the Sword Sharpener

- Sharpening Part 5 – The Sharp Edge

- Sharpening Part 6 – The Mystery of Steel

- Sharpening Part 7 – The Alchemy of Hard Steel 鋼

- Sharpening Part 8 – Soft Iron 地金

- Sharpening Part 9 – Hard Steel & Soft Iron 鍛接

- Sharpening Part 10 – The Ura 浦

- Sharpening Part 11 – Supernatural Bevel Angles

- Sharpening Part 12 – Skewampus Blades, Curved Cutting Edges, and Monkeyshines

- Sharpening Part 13 – Nitty Gritty

- Sharpening Part 14 – Natural Sharpening Stones

- Sharpening Part 15 – The Most Important Stone

- Sharpening Part 16 – Pixie Dust

- Sharpening Part 17 – Gear

- Sharpening Part 18 – The Nagura Stone

- Sharpening Part 19 – Maintaining Sharpening Stones

- Sharpening Part 20 – Flattening and Polishing the Ura

- Sharpening Part 21 – The Bulging Bevel

- Sharpening Part 22 – The Double-bevel Blues

- Sharpening Part 23 – Stance & Grip

- Sharpening Part 24 – Sharpening Direction

- Sharpening Part 25 – Short Strokes

- Sharpening Part 26 – The Taming of the Skew

- Sharpening Part 27 – The Entire Face

- Sharpening Part 28 – The Minuscule Burr

- Sharpening Part 29 – An Example

- Sharpening Part 30 – Uradashi & Uraoshi

Leave a comment