Envy was once considered to be one of the seven deadly sins before it became one of the most admired virtues under its new name, ‘social justice’.

Thomas Sowell

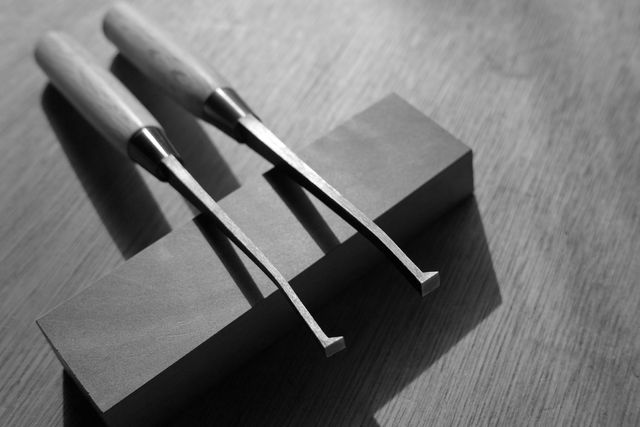

We’ve recently received a long-awaited (and we feared long-forgotten) order of two-handed Ootsukinomi paring chisels from our blacksmith. This post is a simple show and tell.

Your humble servant has scribbled about this tool in this article in our series about the varieties of Japanese chisels

Ootsukino, pronounced oh/tsuki/noh/mee, are large, long-handled paring chisels, the equivalent to the “slick” in the US woodworking tradition, a standard tool for timber framing. It is a rare chisel nowadays, and difficult to make.

This chisel is never struck with a hammer, but is pushed two-handed to pare surfaces and joints in wood to final dimensions. The long handle provides much greater angular control and precision than a standard paring chisel, while the ability to grasp it firmly in two hands makes it possible to effectively employ the greater power of one’s back and legs.

We also carry Mr. Usui’s Sukemaru-brand ootsukinomi, but after looking for a less-expensive option for our Beloved Customers, we ordered these from our Nagamitsu blacksmith over five years ago. Soon after placing the order we despaired of them ever being completed due to the difficulty of forging and shaping them in his advanced years, and did not want to pressure him. But we were surprised to learn recently, indeed after he had retired, that he had actually made significant progress on nine 2-piece sets, lacking only sharpening and handles, and so arranged for them to be completed. At long last they have been delivered.

Yes, this variety of chisel can be procured individually, and Mr. Usui of Sukemaru fame has been kind enough to fill many special orders to meet specific requirements of our Beloved Customer. But the standard way to purchase these in Japan is a 2-piece set, one chisel in 42~54mm blade width and the other in 24mm. We had these forged in the most common 48mm and 24mm boxed sets.

The overall length of both chisels is approximately 640mm (25-13/16″) with a 140mm (5-1/2″) long blade, 160mm (6 -19/64″) neck, and a 340mm (13-25/64″) handle made of an attractive grade of dark-red Japanese red oak. Both chisels have a standard, nicely-formed single ura with the hardened steel lamination properly wrapped up the blade’s sides for the extra toughness and rigidity essential to this tool.

A triple-ura on the 48mm chisel is a useful feature, and we have had Mr. Usui forge his chisels with this detail, but it would have added quite a bit to the cost and so is not available in this more economical brand.

The 48mm chisel is used for paring wider joint surfaces, the cheeks of tenons, and the interior side walls of mortises. It’s the standard mentori beveled-side design seen in our mentori oiirenomi, hantatakinomi and atsunomi.

The 24mm chisel is forged in the shinogi style with a more triangular cross-section to provide clearance for the blade in tight places to pare the many dovetail joints used to attach beams, purlins and bottom-plate (土台) timbers, as well as the end walls of the many 24mm mortises commonly found in traditional timber framing work.

These are not mass-produced tools but hand-forged in Japan from beginning to end by a highly-experienced blacksmith in his one-man smithy using Hitachi Metal’s Yasugi Shirogami No.1 high-carbon steel (White Label No.1 steel), famous for its superior sharpness, ease of sharpening, and sharpness retention performance for the cutting layer, forge-laminated to a softer low-carbon steel body and neck for toughness, typical of all our Nagamitsu-brand products.

These are nicely shaped and finished, top-quality, serious chisels for serious work, but are not suited to everyone. While joiners that make large doors and panels often have a set in their workshop, most cabinetmakers and furniture makers will seldom need such large chisels. But they are one of those tools that when you need them, nothing else will do. Indeed they are indispensable for cutting precise joints in large timbers and joinery, even when those joints are hogged-out using electrical equipment.

At this reduced price, We only have a few sets looking for new masters who will feed them lots of yummy wood, so if you are interested, please contact us using the form below.

YMHOS

If you have questions or would like to learn more about our tools, please click the “Pricelist” link here or at the top of the page and use the “Contact Us” form located immediately below.

Please share your insights and comments with everyone in the form located further below labeled “Leave a Reply.” We aren’t evil Google, fascist facebook, or thuggish Twitter and so won’t sell, share, or profitably “misplace” your information. If I lie may every spoonful of burgundy cherry ice cream I ever eat taste like dirty truck tires.

8 responses to “New Ootsukinomi Paring Chisels”

-

Very nice, Stan. I have a couple of similarly sized ootsukinomi. Besides large joinery, I find that picking one up and waving it around is useful for chasing people out of the shop. It gets their attention.

I have a question about sharpening these. I know that it is easier to remove the handle for sharpening the blade. But after a few rounds of this the handles have become too loose. I have added paper shims inside the mortise for the tang, but that seems a short term solution. Is there a better long term solution, or should I just continue to add shims?LikeLike

-

Thanks for your comment, Gary! I have never waved an ootsukinomi at, or used one to chase away, people, politicians or even pixies (descending order of humanity), but it sounds like a fun time was had by all. Please send link to video! (ツ) An ootsukinomi with a loose handle is extremely irritating, and if it becomes loose enough for the blade to separate from the handle on it’s own at an importune time that pervert Murphy may have a wonderful time dancing naked in puddles of red sticky stuff (sorry, no video). So while I don’t recommend routinely removing the handle after the initial sharpening, I do recommend using a honing jig to help maintain the proper bevel angle on the stones. Most people use a large block of hardwood cut at an angle and inlet to fit the chisel’s face for stability. When the wood becomes worn and the angle skewampus it can be refreshed with a thin angle-cut on a table saw, or maybe a pass or two on a jointer. I suppose the commercially-available jigs like the Lie-Nielson widget (perhaps with jaw extensions?) would work too and last longer, but whatever method used, it requires more physical effort and concentration than a shorter chisel does. Looking forward to the video! Stan

LikeLike

-

-

Thanks, Stan. I have a little sharpening widget that fits the blades but the long handle makes using it awkwardly unbalanced. I’ll go with a shop made hardwood fixture. And I’ll work on that video.

LikeLike

-

You’re right of course about how awkward and over-balanced the handle makes the process. Two options for the block. The first is moving the block/chisel on the stationary stone, and the second is to clamp the chisel/block down and move the stone over the blade’s bevel. The latter takes gear and time to setup, but perhaps yields better results with less risk. 2 drachma.

LikeLike

-

-

COVINGTON & SON

To your humble servant from another humble servant. Let’s not argue our spiritual merits! I enclose a couple of photos of a chisel I sadly only use occasionally. I’m too ignorant to identify its origins but it feels good in the hand when working or not. You might enjoy! Yours Bruce Milburn (convictions in darkness)

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

-

I’d like your opinion on this brand of Japanese waterstone, Ikeda, which has 10 000 grit. Is it all the vendor has made it out to be? I’m thinking of switching from a strop to a 10,000 grit stone . There are several reasons why I desire to change. The most accurate response is that I’ve always been interested in higher grit stones and am eager to compare them to strops.

LikeLike

-

Leave a comment