My relationship to reality has been so utterly skewed for so long that I don’t even notice it any more. It’s just my reality.

Ethan Hawke

The Taming of the Skew

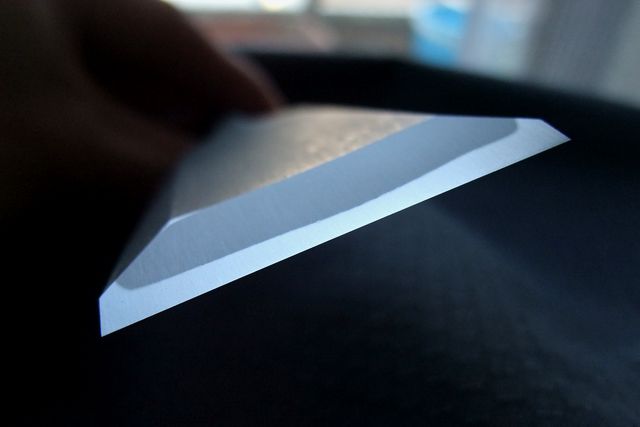

Beloved Customer has of course noticed that it is easier to keep a blade stable when sharpening its bevel if you skew it on the stone. There is nothing wrong with skewing the blade so long as you understand the natural consequences of doing so and compensate for them appropriately. In this article we will examine some of those consequences.

The first and most immediately obvious consequence of skewing the blade when sharpening it is that the blade tends to wear-out, or hollow-out, the center area of the sharpening stone’s face quicker. This is inefficient, wasting time and stones, but can be compensated for if you pay attention and work the blade evenly over the stone’s entire face, including the edges, ends and those pesky corners. BTW, this is not a kindly suggestion but a commandment.

Second, skewing the blade usually results in the nut holding the blade placing uneven pressure on it, with the natural result that the blade wears unevenly, and quite often, develops a skewed cutting edge. Think about it.

In addition, the leading corner is exposed to more fresher, sharper, larger grit particles (which cut more aggressively) than the trailing corner. As a result, the blade’s leading corner tends to be abraded more, causing the blade’s edge to gradually become skewed or rounded in shape over many sharpening sessions. This is definitely bad, and is often mistaken for the work of those devilish iron pixies, especially in the case of kiwaganna and other skewed-blade planes, causing self-doubt, mental anguish, and even piranha in the head (aka “going bananas“). But if you are aware this can happen, and pay attention, you can easily compensate for this tendency thereby avoiding months of expensive psychoanalysis by Dr. Alonzo and the need to consume pallets of his pretty purple pills.

Third, and I have no way to confirm this, I am told by the guys with microscopes that diagonal scratches at the extreme cutting edge leave it a tad weaker, causing it to dull just a bit quicker.

The way to remove problematic diagonal scratches, BTW, is to make the last few strokes on the finishing stone perpendicular to the cutting edge.

So in summary, habitually skewing a blade while sharpening it is not ideal and should be avoided, but is not catastrophic. It will make one’s sharpening efforts a little less efficient and may cause blades and stones to become distorted, but these negatives can be dealt with, at some cost.

Please read the quotation at the top of this article and consider whether or not your sharpening reality has become skewed without your realizing it. Your humble servant confesses, and Dr. Alonzo can confirm, that his was indeed skewed for a long time.

These aren’t things you wouldn’t have figured out for yourself eventually, Beloved Customer, but now, at least if you pay attention, you’re a few years ahead on the learning curve. In the worst case, at least ignorance isn’t an excuse anymore. And there’s always those pretty purple pills to take the edge off (ツ).

YMHOS

If you have questions or would like to learn more about our tools, please click the “Pricelist” link here or at the top of the page and use the “Contact Us” form located immediately below.

Please share your insights and comments with everyone in the form located further below labeled “Leave a Reply.” We aren’t evil Google, fascist facebook, or thuggish Twitter and so won’t sell, share, or profitably “misplace” your information. If I lie may all my mental faculties become hopelessly skewed such that the only occupation I will be fit for is politics.

Other Posts in the Sharpening Series

- Sharpening Part 1

- Sharpening Part 2 – The Journey

- Sharpening Part 3 – Philosophy

- Sharpening Part 4 – ‘Nando and the Sword Sharpener

- Sharpening Part 5 – The Sharp Edge

- Sharpening Part 6 – The Mystery of Steel

- Sharpening Part 7 – The Alchemy of Hard Steel 鋼

- Sharpening Part 8 – Soft Iron 地金

- Sharpening Part 9 – Hard Steel & Soft Iron 鍛接

- Sharpening Part 10 – The Ura 浦

- Sharpening Part 11 – Supernatural Bevel Angles

- Sharpening Part 12 – Skewampus Blades, Curved Cutting Edges, and Monkeyshines

- Sharpening Part 13 – Nitty Gritty

- Sharpening Part 14 – Natural Sharpening Stones

- Sharpening Part 15 – The Most Important Stone

- Sharpening Part 16 – Pixie Dust

- Sharpening Part 17 – Gear

- Sharpening Part 18 – The Nagura Stone

- Sharpening Part 19 – Maintaining Sharpening Stones

- Sharpening Part 20 – Flattening and Polishing the Ura

- Sharpening Part 21 – The Bulging Bevel

- Sharpening Part 22 – The Double-bevel Blues

- Sharpening Part 23 – Stance & Grip

- Sharpening Part 24 – Sharpening Direction

- Sharpening Part 25 – Short Strokes

- Sharpening Part 26 – The Taming of the Skew

- Sharpening Part 27 – The Entire Face

- Sharpening Part 29 – An Example

- Sharpening Part 30 – Uradashi & Uraoshi

Leave a comment