And now at last it comes. You will give me the Ring freely! In place of the Dark Lord you will set up a Queen. And I shall not be dark, but beautiful and terrible as the Morning and the Night! Fair as the Sea and the Sun and the Snow upon the Mountain! Dreadful as the Storm and the Lightning! Stronger than the foundations of the earth. All shall love me and despair!

J. R. R. Tolkien

This article is a continuation of, and probably the conclusion to, our “Sharpening Japanese Tools” series. The last article was one year ago and gave an example of how to employ the lessons taught in the previous 29 posts. At that time, your humble servant promised to discuss the subjects of this article at a later date. It’s later.

Why the delay? Simply because I am an excessively compassionate sumbitch who wanted Beloved Customers who hadn’t already figured out plane blade sharpening on their own to become proficient at regular sharpening operations before worrying about something as bizarre as wacking hard steel blades with hard steel hammers. After all, in the words of Miss Benatar, it’s sometimes a heartbreaker.

But now with the blog teetering on the loose and crumbly edge of the rabbit hole that is the Japanese handplane, we have the choice of either gliding gracefully into its depths or clumsily tumbling down ass over tea kettle (oh my!). Alas, we can tarry balanced in this precarious position no longer.

With his article we will begin our graceful swan-like journey by studying a matched set of operations Beloved Customers need to master to become proficient at maintaining Japanese woodworking blades: one called “Uradashi,” and a related operation called “Uraoshi. If you already have these skills, accept my highest praise. The target audience for this post, however, is those that don’t have experience with uradashi and uraoshi as well as those that want to review and improve the skills they already have.

So spread your wings and fly, my brave cygnets!

Definitions

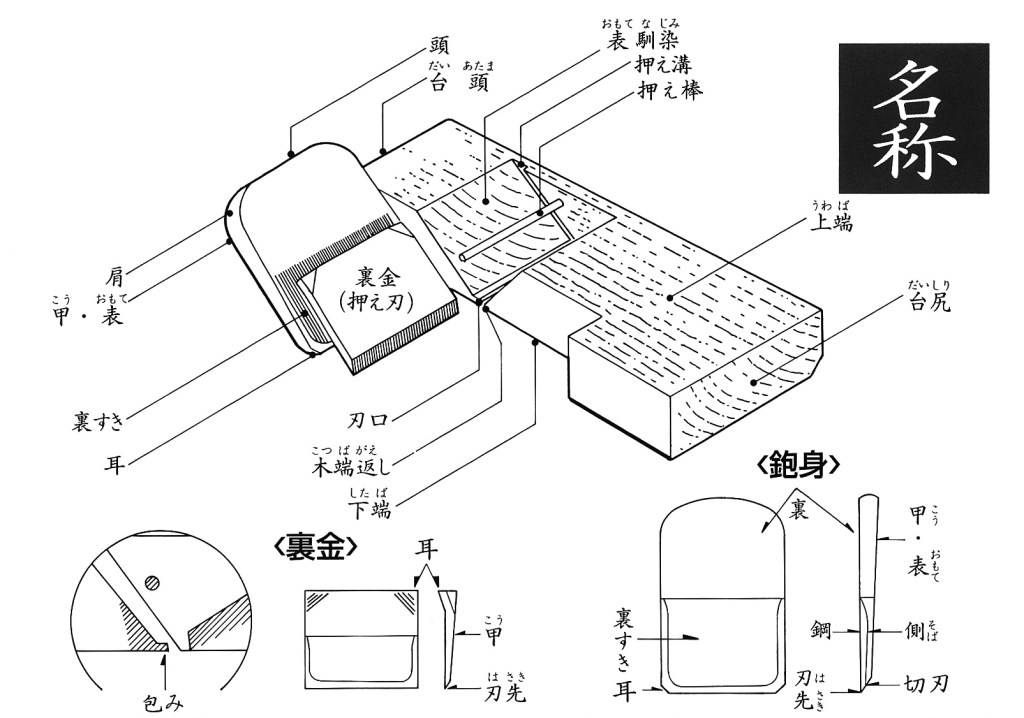

Beloved Customers should already be aware of the hollow-ground “uratsuki,” typical to Japanese chisel and plane blades. If not, please review the article at this link.

Another important term is “Itoura” pronounced ee/toh/oo/rah, which translates directly as “thread land.” This is the polished land on the ura side of the blade across the width of the blade and immediately adjacent to the cutting edge. In fact, it forms one-half of the cutting edge, and the maintenance of this tiny bit of metal is the purpose of the operations described herein.

Uradashi is pronounced oo/rah/dah/she and written 浦出し in the Chinese characters as they are used in Japan. These characters translate directly to “push-out the ura.”

Uraoshi is pronounced oo/rah/oh/she and written 浦押しwhich translates directly to “press the ura.”

These two maintenance operations are performed to restore the blade’s cutting edge to useful condition when the thin itoura land at the cutting edge is almost worn out. We will discuss the why and how below.

Long-term Strategy

Before we start pecking on steel, let’s consider our sharpening strategy.

Professional-grade blades are not only expensive, they are difficult to make, hard to find, and require an investment of time and effort from the user if they are to deliver high-performance results over many years. To minimize the required expenditure of time and effort, and to maximize the benefits achieved we need more than just technique, we need a maintenance strategy.

In previous posts in this series we have discussed multiple strategies, some physical, some psychological, and even a few supernatural ones. The following is one I strongly urge Beloved Customers to adopt:

- Get the ura in good fettle, and then;

- Avoid working the ura on anything but one’s finest-grit sharpening stone thereafter, (with the exception of uraoshi following uradashi, of course).

Simple, no?

The ura is formed by grinding the lamination of extra-hard high-carbon steel to form a depressed area. Because hard steel is time-consuming to abrade, a wise craftsman will work to keep the ura as deep as possible, and consequently the four flat lands surrounding the hollow-ground uratsuki as narrow as possible, for as long as possible, thereby minimizing the area of hard steel that must be abraded with each sharpening.

But no matter how careful we are to preserve the ura, sharpening the bevel makes the blade incrementally shorter, so the day will come, at least in the case of plane blades, when the itoura land becomes as thin as a thread. Once it disappears, the blade will no longer function. This is the only drawback to the Japanese ura feature, and can only be solved by drastic methods.

Bending Hard Steel

The goal of uradashi is to cause the lamination of hard steel at the cutting edge to bend towards the ura so that when we subsequently abrade the bent portion the itoura land will be restored.

Now if you think about this for a second you will realize that trying to bend a thin plate of steel hardened to Rc65~66 without snapping it is a fool’s errand. In the case of Japanese blades it is possible to accomplish but only because of the thicker, supporting layer of soft low-carbon/no-carbon iron, called the “jigane,” to which the hard steel layer is laminated. The other point to understand is that only the portion of the high-carbon steel layer actually directly laminated to the softer jigane can be bent, not the fully-exposed high-carbon steel layer at the extreme cutting edge.

Your humble servant struggled at first with uradashi, in part because every explanation I read about the process in both English and Japanese was written by people who either didn’t really know what they were talking about, or were too lazy to explain it well. Some years, several broken blades, and much heartbreak later I finally figured it out. Better information is available nowadays, but there is still plenty of BS out there to shovel.

Despite the title of this section, the first key point to understand and always remember is that uradashi is not about using a hammer to bend the hard steel layer; Never ever ever never touch this steel with your hammer! I forbid it on pain of 20 lashes with a wet noodle.

Instead, the goal is to peck on the soft iron jigane layer of the laminated blade at the bevel, as described below, deforming it and causing it to expand.

The jigane would normally just deform away from the hammer’s impact point, but the hard steel hagane lamination on the ura side of the blade restrains it causing the entire blade at the cutting bevel to curve in the direction of the ura without snapping or cracking. This is another aspect of the blacksmith’s magic unique to the Japanese plane blade.

The second key point you need to grasp around the neck with both hands and dig your Jimmy Choos deep into is that it is indeed a fool’s errand to try to bend the soft iron lamination by the power of your mighty arm, Oh Lord of Thunder. No, we must be as clever as Loki.

So, how do we cleverly do this job, and what tools should we use?

Tools

You will need the following tools to properly perform uradashi and uraoshi on a blade:

- A small hammer. Great force is neither necessary nor useful; Indeed you must be able to control this hammer very precisely, so the lighter it is the better. One with a pointy end like a funate or a Yamamichi, or a corner of the thin end of a Warrington hammer or tack hammer is ideal because the tiny impact face focuses maximum pressure on a small area, deforming the jigane efficiently. A small, pointy hammer also makes it easier to guide and control the hammer to ensure precise impacts. And control matters a lot because if you miss and strike the hard steel at the cutting edge it will be damaged and bitter tears will flow. Consider yourself duly warned, Oh Might Thor;

- An anvil of sorts. This can be any piece of steel with some mass and with a rounded-over corner. A piece of railroad track is great. I use the face of a small sledge-hammer clamped in my vise. A sharp corner is not good, so round a corner by grinding or filing and then smoothing it. A piece of thin postcard material glued to this rounded corner help keeps the blade from slipping;

- A small square or straightedge;

- A marking pen or scribe to mark the “target area” on the bevel;

- A rough diamond plate/stone or a mild-steel kanaban plate + carborundum powder;

- Parking pen or Dykem for coloring the ura’s lands;

- Regular sharpening tools (stones, water, etc.).

Target Area Layout

Let’s begin by laying out the target area on the soft iron jigane at the blade’s bevel with a marking pen. Or you can scratch lines into the jigane with a metal scribe. This target area will indicate the area you will peck with your little hammer producing many small dents. You must not strike outside this target area even if tempted with donuts. Not even if they have those tasty sparkly sprinkles on top.

The dents you will make with your little hammer need to be limited to a band on the jigane parallel to the cutting edge and beginning 2~3mm from where the jigane lamination begins extending to the end of the jigane lamination at the blade’s back, in the case of plane blades, or the face where the brandname is engraved in the case of chisel blades.

Make a line with your scribe or marking pen the full width of the bevel at this distance from and parallel to the cutting edge. Everything above this line in the direction of the blade’s back, in the case of plane blades, or the face where the brandname is engraved in the case of chisels and knives, is the primary target area. Make sure you get this right.

The dents need to extend across the full width of the jigane layer, except where the corners (ears) have been ground to a bevel at the right and left end of the blade, so the right and left limits of the target area are delineated by the ears.

Although we need to tap the full width of the blade to avoid stress concentrations, there is nothing to be gained by trying to bend the far right and left corners of the blade, so we want to focus approximately 2/3rds of our hammer impacts and the resulting dents near the center 1/3 of the blade’s width. Mark the right and left limits of this central area on your blade with a marking pen or scribe.

The Grip

If you are right handed, hold the blade in your left hand with your index finger extended and pressed against the ura parallel with the cutting edge, and about 5~10mm away from it. Press down with your thumb on the blade’s back clamping the blade between your thumb and the side of your index finger. Your other fingers should support the blade from the ura side.

Your index finger will be the fence that keeps the blade in proper alignment during the tapping-out process.

Next, we need to figure out how to align and move the blade on the anvil, as well as where to place hammer blows in relation to the blade and anvil.

Manipulating the Blade on the Anvil

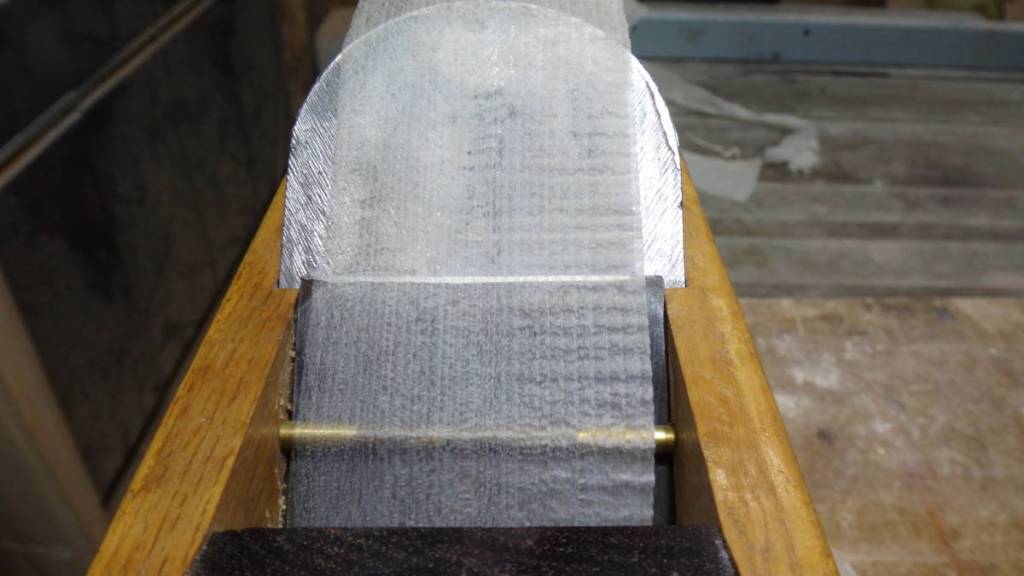

Place the blade’s ura on the rounded corner of your anvil. You may want to tape or glue a piece of thin cardboard, postcard, or manila file folder to the anvil’s corner, not so much as a cushion, but to help prevent the blade from slipping, but this is not mandatory.

Adjust the distance between your extended index finger and the cutting edge as necessary so your finger is touching the anvil stabilizing its position, and so you can slide the blade to the left and right indexing off your finger to keep the target area in proper alignment.

Next, while still in position facing your anvil and with hammer in hand, move the blade aside and tap the rounded corner of your anvil with your hammer lightly. Memorize this location and your position because every tap from now on must be aimed at this same exact spot on the anvil.

The Tap Dance

The time has come to begin the dance.

Reposition the blade on the anvil and use your little hammer to tap the soft jigane layer at the bevel (only the jigane!) in the target area you marked earlier making a row of small dents in it.

These small dents don’t need to be pretty or uniform. Be patient because you may need to make hundreds of pecks, each one quite precisely.

Here is the key point to understand: You want each little dent to cause the jigane to deform and expand in length and width a tiny bit, gradually, until a significant degree of deformation accumulates. The hard steel layer, however, will constrain the jigane layer from expanding, causing the blade to bend, and causing the hard steel layer to deflect and curve towards the ura, bending it without breaking it. It doesn’t seem possible at first, but I promise it will happen, so please be patient.

The trick then is to use the grip described above with your forefinger indexing the blade against the anvil while moving your hand, along with the blade, a tiny bit right or left with each strike, with the each point of impact firmly supported on the anvil, in-line with the hammer blow, thereby squishing the jigane between hammer and anvil. In this way, since the hammer is always aimed at the same exact point on the anvil, you don’t need to worry about realigning it with each blow, removing several difficult-to-control variables from the tap dance at once.

Remember, keep the hammer and anvil precisely aligned, and move the blade left and right, not the hammer. It helps to touch the inside of the elbow of the arm using the hammer against your side in a fixed location to help maintain a consistent hammer swing and distance. Until you have mastered consistency, speed is risky.

Another key point to understand is that, if the point of impact of your little hammer is not directly in-line with the point where the ura on the opposite side of the blade is touching the anvil, the force of the hammer’s impact will tend to cause the blade to jump and wiggle around instead of deforming the jigane. This wastes time and energy and makes it difficult to make precise taps.

Here’s a video of Eleanor Powell tapping away with great control, and with the aid of her faithful Fido. I don’t recommend including a benchdog in your tapping-out routine other than as a deterrent to any pernicious pixies lurking in your workshop eager to cause you to miss with your hammer and chip your blade. Evil pixies!

Here’s a video of Sarah Reich tap dancing with every strike landing precisely in the target area. I need to get a pair of shiny red lycra pants like her to go with my most excellent aluminum foil hat with the curly copper wires and red fringe. Do you think they would make my butt look huge?

Remember, force is neither necessary nor useful. The goals is to make many precisely aligned tiny taps producing many small deformations in the target area, with no impacts on the hard steel layer.

Dent Removal

We talked about “dents” above. If you are using a round-faced hammer, those dents will be little crescents. If you use a hammer with a tiny striking face on one end like a Yamakichi or Funate, that tiny face will dig into the metal making ugly little peck marks instead of pretty little crescents. I have used all varieties of hammers but prefer the ones with pointy ends because their impact face is small and, it seems to me, easier to control. Six of one half-dozen of the other.

But remember that we will abrade away all those dents/pecks/craters after a few sharpening sessions, so appearance is of zero importance.

The Goldilocks Itoura

The goal, of course, is to bend the blade at the ura land just behind the cutting edge enough to create a useful, flat ura. But how wide should the itoura be when the process is complete? Among plane connoisseurs a narrow itoura is, like a willowy super model, considered a thing of beauty. By narrow I mean some where around 0.50~1.0mm.

A narrow itoura does indeed look sexy, so much so that fashion-conscious plane blade blacksmiths make a skinny ura a point of pride. And, in fact, a bulimic itoura makes it easier and quicker to sharpen the blade because the square millimeters of hard steel one must abrade/polish is minimal compared to a wider itoura.

The downside to the super-skinny itoura is that it wears out sooner, making it high maintenance. Now, I’m not suggesting that if your plane blade has a slender itoura it will demand weekly spa visits, twice monthly trips on a G700 jet to the Vienna Opera, annual ski holidays in Verbier, and bi-annual boob jobs, but there is no doubt you will need to do the uradashi tap-dance more often. Shiny lycra pants are optional, but ooh sooo sexy! (シ)

On the other hand, a wider itoura of 3~4mm has some advantages too. It’s easier to fit the chipbreaker (uragane), and you don’t need to do uradashi/uraoshi as often. Much wider than this, however, and I find it can be difficult to get a screaming-sharp edge at times. Moderation in all things, I guess.

I don’t know how to describe when to stop tapping-out the ura to obtain a good width for your itorura because every blade is a little different, but after doing it a few times you will develop a sense of when enough is enough. However, to develop that sense you should make frequent checks on your tapping-out progress by placing your handy dandy straightedge or square right on the itoura parallel to the cutting edge and sighting between the blade and the straightedge/square with a strong light shining at the gap. You will be able to see the itoura gradually bulge upwards at the center. Even a little bit of a bulge will give you a useful itoura, so don’t get carried away.

Uraoshi

Once the tap dance is done, we need to grind down the ura to form a new itoura, a process called “ uraoshi” (ooh/rah/oh/she)

The traditional method is to use the mild steel kanaban lapping plate mentioned above, although any true lapping plate will work. One sprinkles a small amount of carborundum powder on the plate along with a little water, and then works the ura side to side grinding down the bulged area to make a flat.

The problem with using lapping plates and carborundum powder is that not only is it a messy process, but unless you are careful to keep the right amount of wet grit on the plate, the results tend to be a tad irregular. I recommend using diamond plates or ceramic diamond stones (like those made by Naniwa) because they produce more consistent results quicker.

Whether you use a kanaban lapping plate or a diamond plate/stone, it’s important to focus pressure on the thin area where you need the itoura to develop. Pressure anywhere else is not helpful, but only wears out the itoura prematurely.

Here is wisdom: When they first attempt uraoshi most people try to stabilize the blade by applying uniform pressure across the back of the blade. This seems to makes perfect sense, but it always results in grinding a nasty little trench in the two side lands at the ura where it touches the extreme edge of the kanaban or diamond plate. Remember, the uraoshi process tapped out a bit of metal right at the cutting edge, and mostly at its center. This is what you need to abrade, NOT the right and left lands of the ura, and certainly no more than 3~4mm from the cutting edge. So please keep tight rein on your inner badger and carefully focus the pressure you apply during uraoshi only on the thin area where you need to restore the uraoshi.

Some people like to apply a thin strip of paste wax, perhaps 3~4mm wide, on the edge of their kanaban or diamond plate to prevent it from digging ugly trenches in their beautiful and delicate side lands. Others like to apply a thin strip of mylar tape at the same place for the same reason. These techniques all work, but professional sharpeners don’t use them because they know how to apply pressure correctly.

After the itoura has been restored (perfection is not necessary), polish the blade using your normal sharpening routine.

Chisel Blades Versus Plane Blades

Uraoshi and uradashi are operations typically, but not exclusively, performed on plane blades. About the only time chisels need to have uradashi performed is to restore the itoura after the blade receives major damage, like a big chip, a sad event all users of Japanese tools experience from time to time

There is a structural difference between plane blades and chisel blades Beloved Customer must understand when considering performing uradashi on a chisel blade.

Plane blades have a steel lamination that is more-or-less uniform in thickness because that’s all that’s necessary. Chisel blades, on the other hand, are subject to much higher bending stresses than plane blades, so to prevent yielding and failure, traditional chisels are forge-laminated with the steel lamination wrapped up the right and left sides of the blade, forming something akin to a structural steel U-channel, producing a higher moment of inertia, and therefore greater strength and rigidity,

Because of this additional strength, chisel blades are more difficult to bend at the right and left sides using uradashi techniques compared to plane blades. Indeed, they may break if you try.

Since you can hope to safely bend the steel lamination only in areas away from the more rigid sides, uradashi operations on narrow chisel blades will go as smoothly as throwing a cat through a screen door. I wouldn’t even try it on any chisel narrower than 18mm. Beloved Customers have been warned.

If you feel compelled to attempt uradashi on a chisel blade, my only advice is don’t peck within 3mm of the right and left sides.

With this article, our Sharpening Japanese Tools Series is complete (probably). Your humble servant hopes it has been informative. If Beloved Customer had the patience to read it all, and the clairvoyant ability needed to understand most of it, then you know a heck of a lot more on the subject of sharpening than I did when I started the journey. At least you have received some great ideas for sexy new additions to your simply mahvelous woodworking wardrobe!

YMHOS

If you have questions or would like to learn more about our tools, please click the “Pricelist” link here or at the top of the page and use the “Contact Us” form located immediately below.

Please share your insights and comments with everyone in the form located further below labeled “Leave a Reply.” We aren’t evil Google, fascist facebook, or thuggish Twitter and so won’t sell, share, or profitably “misplace” your information. If I lie may Iron Pixies pass gas in my cornflakes every morning.

Links to Other Posts in the “Sharpening” Series

- Sharpening Japanese Woodworking Tools Part 1

- Sharpening Part 2 – The Journey

- Sharpening Part 3 – Philosophy

- Sharpening Part 4 – ‘Nando and the Sword Sharpener

- Sharpening Part 5 – The Sharp Edge

- Sharpening Part 6 – The Mystery of Steel

- Sharpening Part 7 – The Alchemy of Hard Steel 鋼

- Sharpening Part 8 – Soft Iron 地金

- Sharpening Part 9 – Hard Steel & Soft Iron 鍛接

- Sharpening Part 10 – The Ura 浦

- Sharpening Part 11 – Supernatural Bevel Angles

- Sharpening Part 12 – Skewampus Blades, Curved Cutting Edges, and Monkeyshines

- Sharpening Part 13 – Nitty Gritty

- Sharpening Part 14 – Natural Sharpening Stones

- Sharpening Part 15 – The Most Important Stone

- Sharpening Part 16 – Pixie Dust

- Sharpening Part 17 – Gear

- Sharpening Part 18 – The Nagura Stone

- Sharpening Part 19 – Maintaining Sharpening Stones

- Sharpening Part 20 – Flattening and Polishing the Ura

- Sharpening Part 21 – The Bulging Bevel

- Sharpening Part 22 – The Double-bevel Blues

- Sharpening Part 23 – Stance & Grip

- Sharpening Part 24 – Sharpening Direction

- Sharpening Part 25 – Short Strokes

- Sharpening Part 26 – The Taming of the Skew

- Sharpening Part 27 – The Entire Face

- Sharpening Part 28 – The Minuscule Burr

- Sharpening Part 29 – An Example

- Sharpening Part 30 – Uradashi & Uraoshi

Leave a comment