The edge separates the average from the exceptional.

Anon

In this installment in our series of articles about Japanese handplanes, your most humble and obedient servant would like to present one of the most useful woodworking tools of Japan, the adjustable chamfer plane.

Terminology

In Japanese this handplane is called a kadomenganna, written 角面鉋 in Chinese characters. “角Kado” means “corner,” “面 men” means “surface,” and “鉋 ganna” is a tweaked pronunciation of “kanna” which means “handplane.” Since it’s mainly used to cut 45˚chamfers on the 90˚ corners and edges of wooden objects, and being fully adjustable, I choose to call it an “adjustable chamfer plane” in English. I beg Gentle Reader’s kind undulgence.

Components

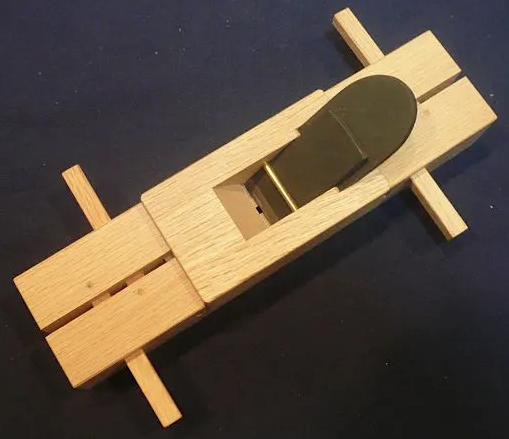

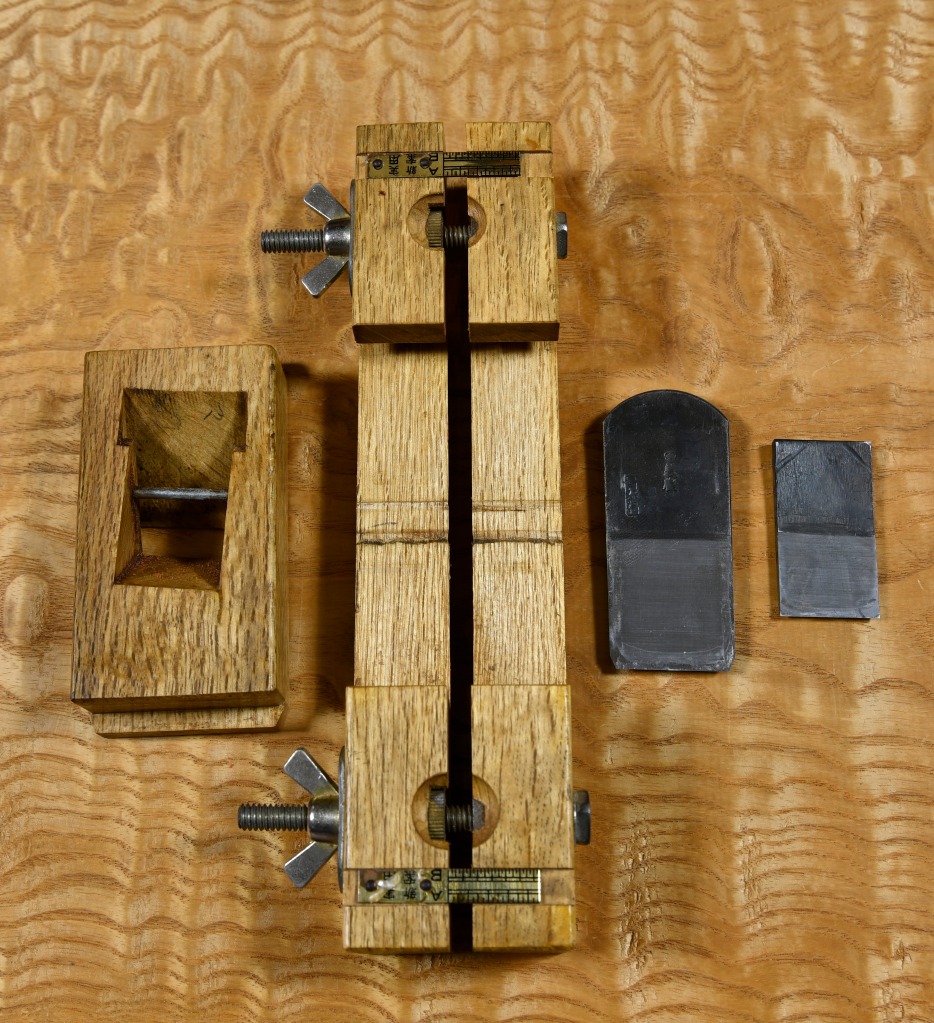

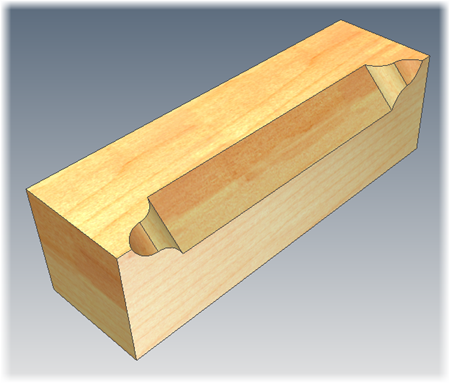

The modern Japanese chamfer plane, which is the only type we currently carry, is comprised of a small block of white oak housing a relatively narrow laminated steel blade as well as a chipbreaker.

This block (aka “dai” 台 in Japanese) fits into a “carriage” comprised of two sticks of white oak joined by steel and brass nuts and bolts held in place by captured wing nuts. The block fits tightly into grooves cut into the carriage so the user can shift the block and its blade right or left as necessary to either accommodate the required width of cut, or to expose a sharp portion of the blade when one portion becomes dull.

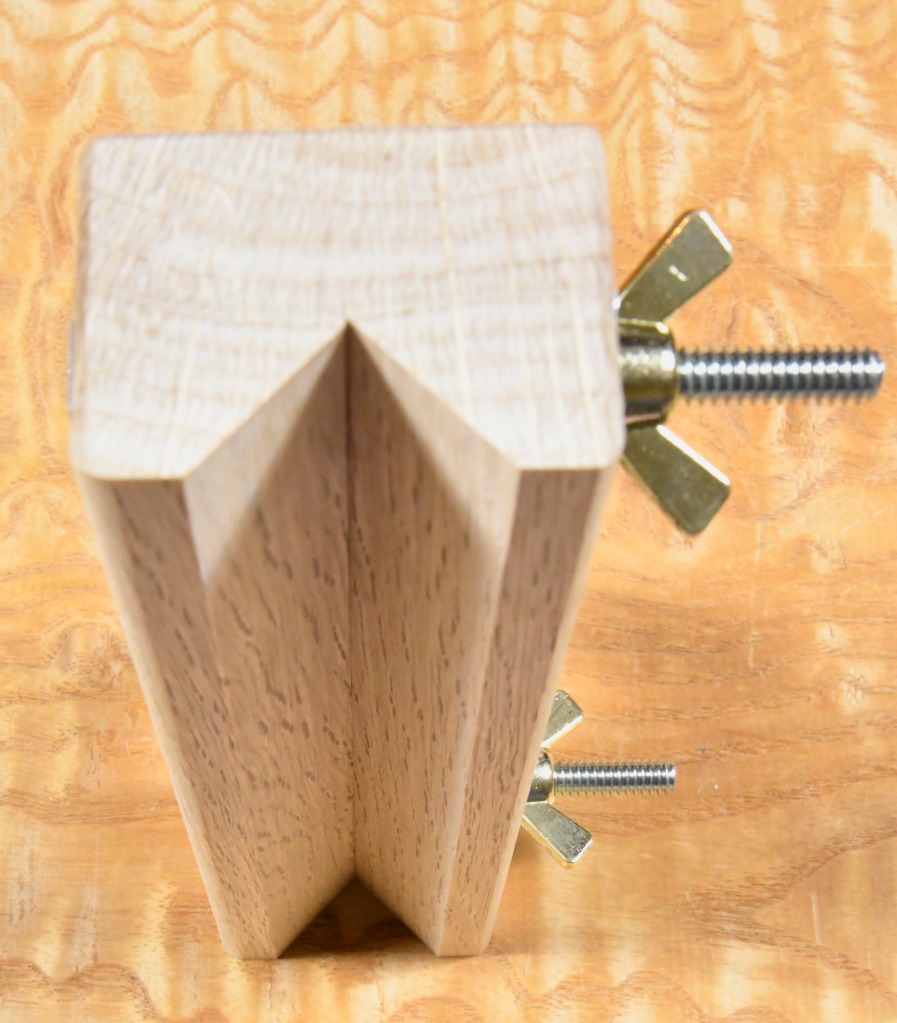

The width of cut can be quickly adjusted from zero to 24mm wide by rotating the two wing nuts smoothly opening or closing the gap between the two legs of the carriage. Eazy peazy Japaneezy.

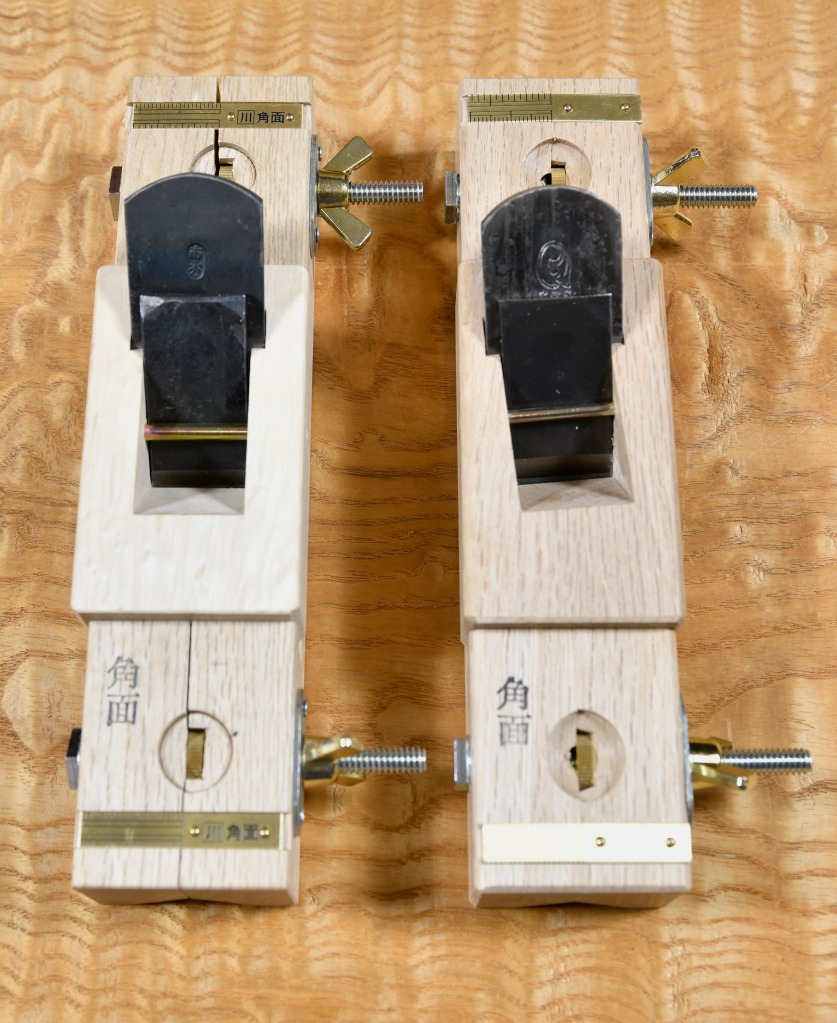

The most common variety of chamfer plane has a blade inlet into the block with its mouth oriented 90˚ to the direction of travel. The next most common variety has a blade that is slightly skewed to produce a smoother cut with less tearout. We carry both types.

Uses for the Chamfer Plane

Japanese chamfer planes are essentially molding planes with two mutually adjustable fences used to produce chamfered edge treatments on wooden objects. Molding handplanes typically have blades ground to specific profiles intended to plane the edges and corners of wooden objects. Some produce purely decorative, curved shapes such as the Roman ogee, while others produce functional and/or structural edges such as tongue and groove joints.

But 45˚chamfer planes have a simple straight blade intended to produce a flat surface at 45˚ to the adjacent faces of the board. However, some varieties are used to cut chamfered surfaces at various angles.

Once cut this 45˚ chamfer is often left as-is in many projects and especially structural wood members as a finished surface. It tends to make make the board, beam or column look more refined. It also prevents the corners from being easily chipped or torn off, a safety feature in some cases. A hard 90˚ corner in exposed wood is seldom durable and given time and abuse often becomes ouchy.

Nowadays the electric router has sadly replaced practically all molding planes, and although I haven’t used an electric router in 15 years or so, I won’t deny they are very useful tools even if they are ultimately more expensive, destroy the user’s inner peace along with their hearing, fills their lungs with dust, chews their fingers, leaves unsightly ripple marks on the wood, and goes through expensive bits like Homer Simpson does donuts… mmmm donuts.

But routers are not all evil, for they do have the advantage of being able to treat the inside surfaces of curved edge whereas the plane under consideration can only do straight edges and outside curved surfaces. Of course, it’s possible to make chamfer planes that cut inside curved surfaces like those used by coopers (barrel makers).

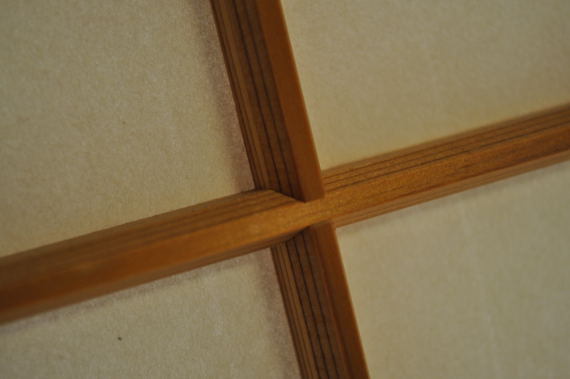

The Joinery Chamfer Plane

As mentioned above there are a very few varieties of specialty chamfer planes long used in joinery to produce different angles. Why angles other than 45˚ you say? Ah, perspicacious as always. Well, a simple 45˚ chamfer sheds dust and water well, but in the case of windows, doors and shoji, for example, it removes too much wood weakening mullions and kumiko to the point of structural frailty, and often appears less refined to boot. Sadly, these are no longer being made and are hard to find.

Advantages

As I suggested above, the chamfer plane produces lots of of fragrant shavings but little unhealthy dust. It won’t make your fingers bleed, and won’t grab your clothes.

Indeed, I can still remember the night I was working late on a custom door using a 15amp 1/2″ collet electrical plunge router with a long 3/4″ Ø carbide bit to cut deep mortises. This was before the days of automatic mechanisms to stop the spinning mass of copper and steel that is the armature when the power switch is released. Suddenly, out of pure evil malice, the howling beast grabbed my loose soccer jersey nearly chewing a hole in my chest! Ah, good times!

The chamfer plane works slower than a router, but it won’t gouge your work if you loose concentration for a second, it won’t make burn marks on your boards, or cause She Who Must Be Obeyed to lob complaints about racket and dust at you like barbed arrows smeared with toxic tree frog goop. To the contrary, it’s an efficient, well-behaved, forgiving, even gentle tool, one that produces a flat, sometimes even shiny surface with perfectly crisp edges on wood instead of the burnt and pounded washboard surfaces violent routers often inflict.

Another advantage to the Japanese chamfer plane is its relative light weight and small bulk, compared to the bulky, clunky, mind-numbing electrical equivalent. Much easier to store in the toolbox or work apron. And of course, being a simpler and more honest tool, it’s much less likely to be commandeered by Murphy’s painful pointy purple pecker to wreak death and destruction.

And of course, while its blade does need to be sharpened occasionally, the chamfer plane will provide many decades of continuous service without having to purchase a single nasty spinning bit from the CCP.

While it incorporates a couple of bolts, it has no cord and needs neither piggish chargers, nor poisonous batteries. It is a tool in total denial of the principles of planned obsolescence, predetermined service life, corporate profitability and hidden environmental destruction advocated by the high priests of profit at the Harvard School of Business and Monkey Butts. One might even say it’s a pragmatically contrarian tool. But whatever you choose to call it, I call mine a faithful servant, indeed, a friend.

How to Adjust

Adjusting the width of the chamfer is accomplished by first loosening the two wing nuts on the bolts. If increasing the width of cut, continue to spin the wingnuts out. Then once the gap between the legs is the right width, set the locknuts to the right position, check that the legs are parallel either by using a caliper to measure the distance between the legs at the front and rear of the carriage, and lock the legs in place using the wingnuts.

These planes have graduated brass indicators inlaid across the front legs and another across the rear sides of the carriage that are useful for rough use, but should not be relied on for precise settings.

Alternately, you can rest the plane on the corner of the board and examine the gap between the legs and board. If a significant gap exists, simple adjust the wing nuts until it closes.

When considering the purchase of a chamfer plane, be sure it has a brass plate inlaid in front of the mouth to prevent wear at this high-pressure area.

When you receive your chamfer plane, the block should fit tightly into it’s carriage. This will loosen with use, or applying a bit of oil or wax on the tongues of the block will help. Worse case, use a metal file and a bit of 220grit sandpaper to lightly adjust the width of the tongue.

When removing the block from the carriage, please do not use a steel hammer to strike the block. A wooden mallet works well, but holding a small block of softwood, like the one shown in the photo above, as a cushion between hammer/mallet and plane is best.

A Professional Technique

Quite frequently we need to cut a stopped chamfer, whether it’s for a lambs tongue chamfer detail or where stile meets rail in joinery. In any case, when we need to judge exactly where the blade of our planes starts and stops a cut, it helps to make marks on the chamfer plane’s legs indicating the location of the cutting edge, and corresponding pencil marks on the workpiece, to help with starting and stopping chamfer cuts in the right place.

Summary

The Japanese kakumenganna 45˚chamfer plane is a lightweight, compact, safe, healthy, cost efficient, environmentally sustainable and pleasant tool for quickly cutting chamfers in wood without leaving ugly ripples or burn marks on the wood, or ruining our hearing, or filling our lungs with sawdust. I couldn’t work without mine.

YMHOS

Link to Pricelist and pics of the Japanese Adjustable Chamfer Plane

Other Posts in the Japanese Handplane Series:

- The Kiwaganna Skewed Rabbet Plane

- Part 1: East vs. West

- Part 2: Blade Adjustment

- Part 3: The Blade

- Part 4: Fitting Blade & Body

- Part 5: The Chipbreaker

If you have questions or would like to learn more about our tools, please click the “Pricelist” link here or at the top of the page and use the “Contact Us” form located immediately below.

Please share your insights and comments with everyone in the form located further below labeled “Leave a Reply.” We aren’t evil Google, fascist facebook, or or the IT manager for HRC’s bathroom server farm, and so won’t sell, share, or profitably “misplace” your information. If I lie may all my chamfers chip and become slivers in my fundament

Leave a comment