The expectations of life depend upon diligence; the mechanic that would perfect his work must first sharpen his tools.

Confucius

In this article in our series about sharpening Japanese woodworking blades your always humble and obedient servant will try to bring all the information provided in previous articles together into a single practical example. That does not mean the entire contents of those articles are repeated here, however, so please refer to the previous articles if things become confusing. I have provided some links in the text, and provided links to all the articles at the end.

But before we dive into our practical example, I would like to create some context.

Paying Debts

The purpose of this blog, as I have mentioned before, is not to sell stuff or attract clicks but to help our Beloved Customers increase their knowledge and improve their skills in maintaining and using the high-quality hand-forged professional-grade woodworking tools we purvey.

Another purpose is to pay a debt of the kind that can’t be recorded on paper, only in the heart.

In this series of posts I have carefully NOT promised quick and easy results, nor have I given abbreviated explanations or promoted dumbed-down techniques tailored to fit neatly within the publishing parameters of a book, magazine article, or a pretty little video. This is because the series is not about me, or my skills, or what I think is best, or selling stuff but rather helping our Beloved Customers obtain real long-term results and life-long skills of the sort expected of professional Japanese woodworkers. And since I can’t instruct them directly, our Beloved Customers must truly understand the principles and techniques so they can train themselves. Fragmentary instructions and short-cuts would be far easier to write about, but risk creating more confusion than progress.

I share many experiences in common with most of our Beloved Customers, but I’ve also had some unusual experiences working with and being mentored by extremely accomplished Japanese professional craftsmen including sword sharpeners, tool sharpeners, carpenters and joiners. None of those gentlemen charged me a notched nickle for their instruction. Likewise, I have never sought compensation for teaching others those same techniques. And so we come to the other reason for this series, namely to pay those gentlemen back for the time they spent and the kindness they showed me.

So gird up your loins, recall the information and techniques presented in the previous 28 articles in this series, and let’s sharpen a blade.

Removing Damage and Correcting the Bevel

I will not even try to deal with all the possible starting points for sharpening a woodworking blade, but in this example we shall assume a starting point of the lands surrounding the hollow-ground area at the blade’s ura being already flat, planar, and polished. If your blade is not in this condition, follow the instructions at the end of this section. We shall also assume the edge has a small chip that must be removed first. These conditions will cover 80% of sharpening jobs.

If the blade’s cutting edge bevel angle is where you want it to be, the bevel is already flat, and the blade isn’t damaged, please skip to Step 11 below.

1. Examine the Bevel Angle: Check the bevel angle with your bevel angle gauge. 27.5° ~ 30° for plane blades, 27.5° ~ 35° for oirenomi and atsunomi. No less than 24° for paring chisels.

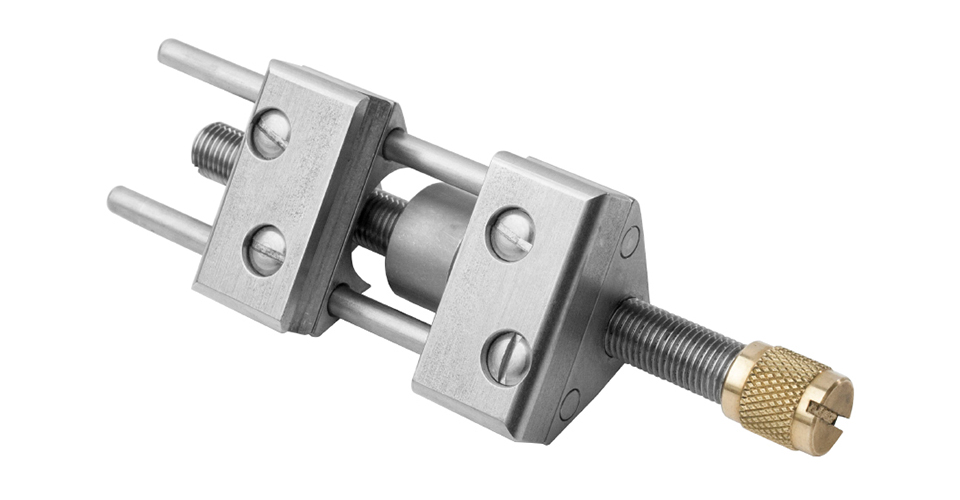

2. Correct the Bevel Angle: If, based on your check in the previous step and the blade’s actual performance, you determine the bevel angle needs to be adjusted, correct the bevel angle using your 400~800 grit diamond plate or diamond stones or FLAT carborundum stones either free-hand or using a honing jig like the Lie-Nielson product, the Eclipse jig, or whatever catches your fancy. If you use a honing jig, you may want to add a drop of oil to the moving parts before they get wet. Be careful to avoid making a skewed or curved (cambered) cutting edge unless that is specifically what you need.

3. Examine the Edge: Examine the blade by eye and touch. Stroke the cutting edge with your thumb (over and away from the edge not towards the cutting edge!) to confirm its condition, and run a fingernail along its length to check for defects as described in the previous post in this series. Your fingerprints will snag on any rolls or burrs, and your fingernail will detect irregularities invisible to the eye. Assuming there is some minor damage, go the next step. If there is no damage, the bevel is in good shape, and the blade is just dull, skip to step 11 below.

4. Remove Damage: Remove chips and dings from the cutting edge by standing the blade, cutting edge down, on a flat 1000 grit stone, with ura facing away from you, tilted a few degrees from vertical towards you, and pull the blade towards you without applying downward pressure. Usually one or two light strokes will suffice. The goal is to remove damage by creating a flat at the cutting edge. Examine the flattened edge with eye, fingertip, and fingernail to see if the chip or defect has been removed. Repeat until it’s gone. Don’t overdo it. Whatever you do, don’t allow the blade to become skewed! This method takes a bit of courage the first time, but it is the quickest, surest, and most economical way to get the job done.

5. Clean the Blade: Carefully clean grit and mud from the blade and the honing jig’s wheel (if you use one) to prevent contaminating the next stone. This is important.

6. Check and Color the Bevel: Check the bevel frequently to confirm full contact. You might blacken the bevel with a marking pen or Dykem to make it easier to monitor progress. This step is worth repeating between stones because it is helpful in monitoring what you cannot see otherwise.

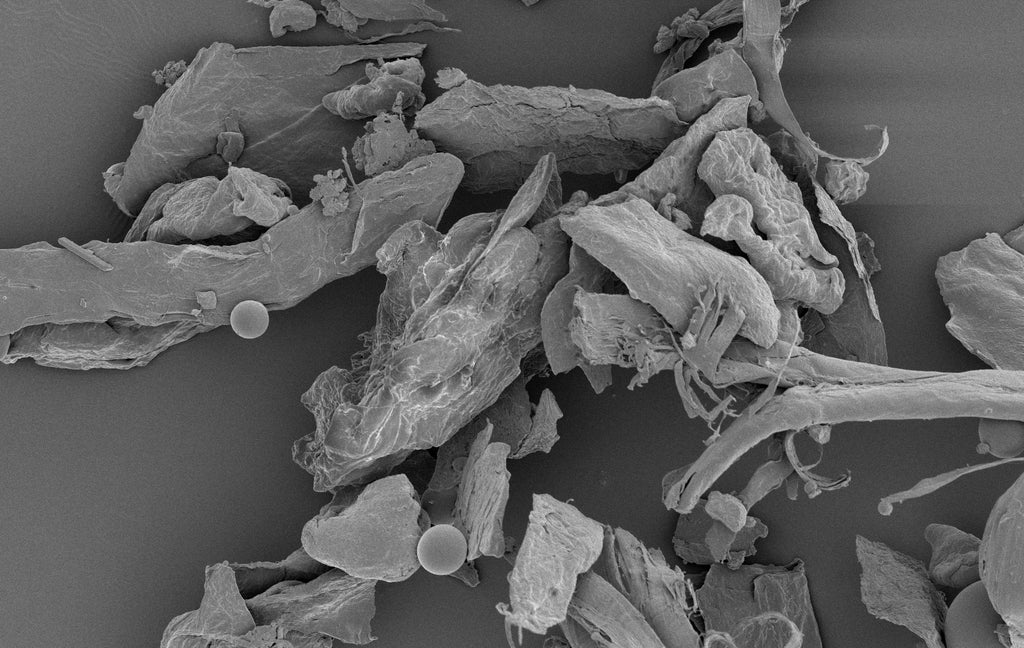

7. Sharpen on the Rough Stone: This is the most important stone in the process. Now that all the damage has been removed and the bevel is flat and in good shape, we need to abrade the bevel until the flat we made in step 4 is gone and we have created a minuscule, tiny, clean burr. Sharpen the blade’s bevel on your roughest diamond plate or FLAT carborundum stone. If sharpening freehand, take short strokes. Always use the entire face of the stone, including corners, edges and ends as described in the previous post in this series. Turn the stone end-for-end frequently to compensate for your natural tendency to work some areas of the stone harder than others. Watch the edge carefully to make sure the width of the flat made at the cutting edge in Step 4 above gradually decreases in width evenly along the cutting edge’s length. If the flat becomes narrower at one corner than the other, apply extra pressure at the wider side, or hang the corner of the blade’s narrower side off the stone for a few strokes to correct. Stop when the flat is gone, and a clean, uninterrupted, but barely detectable burr is created. With practice, you should be able to do this without a honing jig. When using all the stones and plates in this process, keep them wet at all times, and add water as necessary. If the stone becomes dry, not only will it clog and stop cutting efficiently, but friction may cause localized heating of the thin metal at the cutting edge softening it. Remember, you’re violently tearing metal from an extremely thin cutting edge. You cannot see it and your fingers cannot feel it but this destruction heats up metal at that thin edge, so cool it down with water.

8. Check the Burr: Your fingertip will feel the burr long before your eye can see it. Stop when you have a small, uniform burr without interruptions the full width of the blade. Confirm this with your fingernail. Anything beyond this is just wasting metal and stones. With practice, this process will go very quickly, and you can move onto the next stone while the burr is barely detectable.

9. Create Skewed Scratches: When you have a uniform burr, work the blade sideways, or at an angle, on the stone to create diagonal scratches on the bevel removing the straight-on scratches the stone produced.

10. Clean the Blade: Wipe and wash the blade (and the honing jig’s wheel, if you are using one) to remove grit and mud. This is very important to prevent contamination of finer-grit stones.

At the conclusion of step 10, the bevel will be flat, uniform, and at the correct angle. The flat you created on the cutting edge during step 4 above will be gone, and you will be able to just detect a full-width tiny burr using your fingers.

For the next steps, keep the blade attached to the honing jig if you used one in the previous steps. Otherwise, sharpen freehand if you can. Don’t let the honing jig become a crutch that slows you down and prevents you from developing control.

Normal Sharpening Procedures

This is where the sharpening process normally starts when the blade is not damaged and the bevel is in good shape but only needs to be sharpened. It usually does not include a honing jig which can only slow things down.

11. Check and True the Medium-Grit Stone: You may decide to use more than one medium grit stone. I mostly use a 1000 grit at this stage, but may use a 2,000 grit stone as well. Whatever stone you use, it must be clean and flat. As described in previous posts, you need to check the flatness of your stones frequently with a stainless steel straightedge. To do this, wash any mud off the stone and pad (don’t rub) the stone’s face dry with a lint-free clean cloth or paper towel. Hold the stone up to a light source, place the straightedge along the stone’s length, across its width, and across diagonals to check for light leaking between stone and straightedge. Make a pencil mark, such as a line or circle, on high spots using a wide carpenter’s pencil. Once you understand if and how the stone’s face is distorted, flatten it using whatever method you prefer, a diamond plate/stone, a specialized truing block, or my preferred method, another stone of the same grit. If you use my method you won’t need to worry about grit contamination and can save time and money by truing two stones at the same time. Six of one, half-dozen of the other.

12. Sharpen on the Medium-Grit Stone(s): Work the blade’s bevel on your medium-grit stone in short strokes using the stone’s entire face from side to side, end to end, and corner to corner, turning the stone end-for-end frequently and being careful to avoid rocking the blade. A bulging bevel is bad news, Bubba. You will know you are done with this stone when all the diagonal scratches from the previous stone, especially at the extreme edge, have been removed. The burr may or may not have evaporated by now, so check with your fingerprints and fingernail. If it still remains, it should be just barely detectable. If it is still big, you need a few more strokes on this stone to shrink it. Using a loupe at this point will be informative. End your work on this stone by creating some new diagonal scratches on the bevel erasing all the previous straight scratches.

You may want to repeat this step using another medium-grit stone, such as 2,000 grit, to save wear on your finishing stones. Either way is fine.

13. Clean the Blade: Wipe and wash the blade (and the honing jig’s wheel, if you are using one) to remove grit and mud. This is especially important at this stage in the sharpening process. Remove the honing jig at this point if you have been using one.

14. Polish on the Finishing Stone: Move onto your finishing stone, usually a 6,000~10,000 grit synthetic stone. This may not or may not be the final finishing stone you choose to use. Be sure it is flat, uncontaminated with grit from rougher stones, and wet. You may want to use your nagura stone to create a slurry from the stone’s corners and edges that will accelerate the polishing process. Be sure to keep the blade’s bevel in close contact with the stone’s surface on both the push and pull strokes. When all the diagonal scratches from the previous stones are gone, you are done with this stone. If there is still a burr left after the medium-grit stone, it should have evaporated by now. If not, the burr was probably too big to begin with and your technique needs refinement.

15. Examine the Bevel: Take a good look at the polished bevel. Are there still scratches left from the previous stone? This may be because you did not remove all the scratches from previous stones. Or it could be because this stone or previous stones in the series were contaminated with dust or rougher grit. If so, you should figure out why and correct the cause before the next sharpening session.

16. Polish the Bevel Using the Final Finishing Stone: This step may not be necessary, depending on the time available, the degree of sharpness required, and your inclinations. This extra polish probably won’t make a significant difference in the cutting tool’s cutting performance so is often abbreviated during a busy work day. If you use a natural finishing stone or a 10,000+ grit finishing stone, this is the time to use it. Simply repeat the process in step 14 above, but be sure to apply light pressure, keep the stone at least a little wet, and sharpen on both the push and pull strokes. The final finishing stone serves a polishing function, and because it’s grit is so fine, it lacks the ability to distort the bevel badly, so you can take longer strokes and polish the blade on both the forward and return strokes.

17. Polish the Ura: With the bevel polished as finely as you intend it to become, polish the ura on the final finishing stone only. Place the last 1/2” of blade’s length on the stone’s edge (the stone MUST be flat) with the cutting edge parallel with the stone’s length, and the rest of the blade hanging off the stone but supported by your right hand. Press down on the bevel with two or three fingers of your left hand. Be sure to apply even pressure with these fingers. These fingers press down only and do not move the blade. The right hand pushes the blade back and forth and onto and off-of the stone. Take light strokes focusing pressure on the extreme cutting edge, but without lifting the blade’s head.

18. Polish the Bevel (Again): After several strokes on the ura, polish the bevel.

19. Alternate Between Ura and Bevel: Go back and forth polishing the ura and bevel, but keep in mind that you want to limit the number of strokes on the ura side (assuming it’s already highly polished as discussed above).

20. Examine the Edge: Check the full length of the cutting edge frequently with your eyes, fingertips and fingernail. The burr should be gone entirely. The edge should be sharp, and absolutely smooth. All the rougher scratches from previous stones should have disappeared. I make a final sharpness test by shaving an ultra-thin slice of skin from a callous on a finger allowing my bones to sense the degree of sharpness. This method is much more accurate than shaving hair off the arm. If you try it please don’t draw blood.

21. Clean, Dry and Oil: After you are done sharpening the blade, rinse it with clean water or sharpening solution (Item 5 in Post 17) and wipe it dry on a clean cloth or paper towel. You may want to strop it lightly on a soft clean cloth (or the palm of your hand, if you are confident in your abilities) to remove hidden water. I recommend applying a spray liquid rust preventative to the blade that displaces moisture, such as CRC Industries’s 3-36 or WD-40. CRC3-36 is paraffin based, floats water out of the blade’s nooks and crannies, and leaves a film that will prevent corrosion long term. However, please note that, while WD-40 is readily available, very convenient and displaces moisture, it evaporates entirely and is therefore not adequate for long-term corrosion protection. If you are going to use the blade right away, a little oil from your oilpot is cheap, convenient, and will do the job just fine.

With practice, and assuming you have not let your stones become too distorted, this entire process from Step 1 should take no more than 10~15 minutes. This assumes the blade is chipped or damaged and you need to correct the bevel or use a honing jig. Honing jigs slow the process down but are convenient when using rough stones and coarse diamond plates.

If the blade is in good shape and just needs normal sharpening, the goal should be 5 minutes from the medium grit stone in step 11. If you can’t do it that quickly right away, don’t rush, just practice and get a little quicker each time: Remember the turtle with the sail: Festina Lente: Slow is smooth; Smooth is fast.

Note: If you are sharpening a new blade, or the ura needs to be trued and/or repaired, work the ura on all the stones used in the steps above, but be careful to limit the number of strokes on the rougher stones to the absolute minimum. Also, instead of keeping just 1/2” of the blade’s length on the stones, move it diagonally in and out towards the blade’s center to prevent the stones from digging grooves into the lands at the right and left of the ura. Use special care during this process.

I recommend covering at least your finishing stone with something when you are not using it to protect it from contaminating dust. I simply wrap mine in a sheet of newspaper. It doesn’t take any time or money. Some stones prefer to read the sports pages, others prefer current affairs or the fashion page. Mine seem to like the funny pages. Just ask them.

Conclusion

I am confident the techniques described in this series of posts will prove useful if sharp tools matter to you. Your tools may not talk much, but if you train yourself in these techniques I promise they will sing their appreciation.

I trust the gentlemen that taught and mentored me would be pleased with the content in this series of articles, although I doubt they have time for reading nowadays. I’ll make the introductions, so let’s ask them when we meet again in the big lumberyard in the sky.

In the next and final article in this series, we will consider how to restore a worn-out ura in a plane (and maybe even a chisel) blade. Is there no end to the excitement? Until then, I have the honor to remain,

YMHOS

If you have questions or would like to learn more about our tools, please click the see the “Pricelist” link here or at the top of the page and use the “Contact Us” form located immediately below.

Please share your insights and comments with everyone in the form located further below labeled “Leave a Reply.” We aren’t evil Google, fascist facebook, or thuggish Twitter and so won’t sell, share, or profitably “misplace” your information. If I lie may Mama Shishi bite my head off.

Links to Other Posts in the “Sharpening” Series

- Sharpening Japanese Woodworking Tools Part 1

- Sharpening Part 2 – The Journey

- Sharpening Part 3 – Philosophy

- Sharpening Part 4 – ‘Nando and the Sword Sharpener

- Sharpening Part 5 – The Sharp Edge

- Sharpening Part 6 – The Mystery of Steel

- Sharpening Part 7 – The Alchemy of Hard Steel 鋼

- Sharpening Part 8 – Soft Iron 地金

- Sharpening Part 9 – Hard Steel & Soft Iron 鍛接

- Sharpening Part 10 – The Ura 浦

- Sharpening Part 11 – Supernatural Bevel Angles

- Sharpening Part 12 – Skewampus Blades, Curved Cutting Edges, and Monkeyshines

- Sharpening Part 13 – Nitty Gritty

- Sharpening Part 14 – Natural Sharpening Stones

- Sharpening Part 15 – The Most Important Stone

- Sharpening Part 16 – Pixie Dust

- Sharpening Part 17 – Gear

- Sharpening Part 18 – The Nagura Stone

- Sharpening Part 19 – Maintaining Sharpening Stones

- Sharpening Part 20 – Flattening and Polishing the Ura

- Sharpening Part 21 – The Bulging Bevel

- Sharpening Part 22 – The Double-bevel Blues

- Sharpening Part 23 – Stance & Grip

- Sharpening Part 24 – Sharpening Direction

- Sharpening Part 25 – Short Strokes

- Sharpening Part 26 – The Taming of the Skew

- Sharpening Part 27 – The Entire Face

- Sharpening Part 28 – The Minuscule Burr

- Sharpening Part 30 – Uradashi & Uraoshi

Leave a comment