Outside of a dog, a book is man’s best friend. Inside of a dog it’s too dark to read.

Groucho Marx

Natural sharpening stones are wonderful things. At least the good ones are. Finding one that works well with our blades and sharpening style is a thrilling experience and a source of long-term joy. Such an excellent stone can be hard to find and will often be expensive, but whether dirt cheap or worth rubies, it will be delicate and need protection.

In a previous article we looked at how to select a natural Japanese sharpening stone: Sharpening Part 14 – Natural Sharpening Stones

In this article we will examine some methods to ensure your natural sharpening stone provides you long reliable service. Your humble servant suggests you read this article aloud to your favorite stone to gauge its reaction. If you pay close attention, you may even see it wiggle just a tiny bit with gleeful anticipation, especially when you get to the parts about calligraphy, color selection, and skirts. Stones can be very fashion conscious, you know.

The Weaknesses of Natural Stones

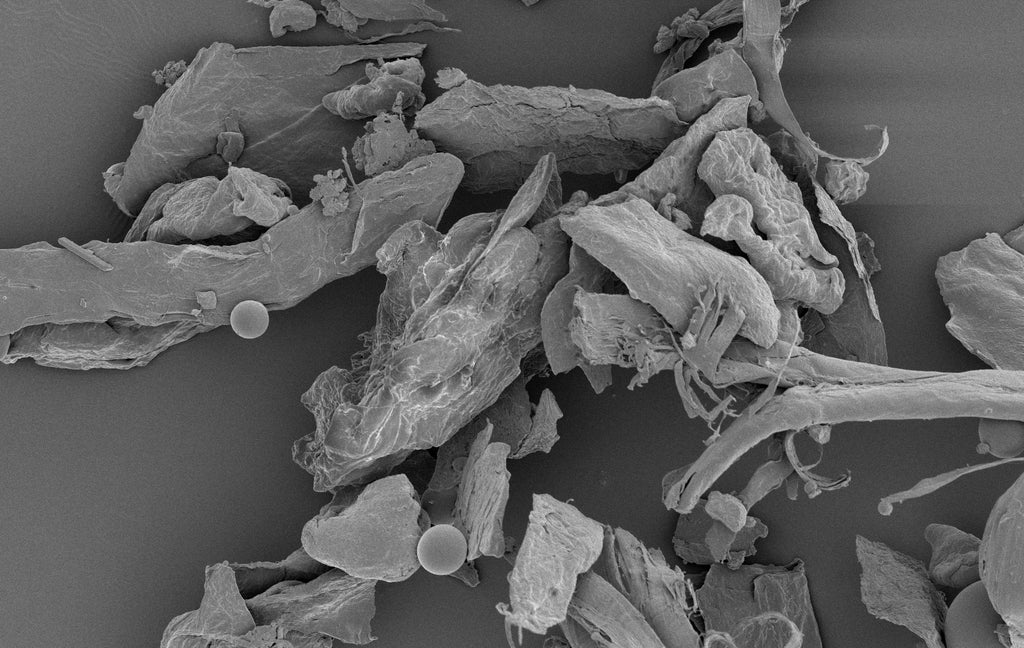

The first thing to keep in mind is that Japanese natural stones are pieces of sedimentary layers that formed on the bottom of the ocean, essentially red-hot dust violently spewed high into the atmosphere by volcanoes, sifted and sorted by wind and waves and distance, and laid down on the seabed like pages in a book. They have defects even if you can’t see them. They naturally have top and bottom surfaces as well as side/end surfaces where the layers are exposed. Water tends to soak in-between these layers exposed at side and end surfaces sometimes causing the layers to separate and even crack in heartbreaking fashion.

Combined with the relative softness of the mineral particles, this structure makes most Japanese natural sharpening stones fragile.

The Stone Base: Objectives and Materials

So what can we do to avoid and/or mitigate these risks to our precious stones to ensure they are happy and will last a long time?

The most important thing you can do to protect your stone is to make a durable base, and to attach your stone firmly to it. The base provides several benefits:

- Seals the stone’s underside from water penetration, reducing the potential for separation and cracking;

- Provides structural support reducing the risk of cracking, especially as the stone becomes thinner;

- Makes the stone easier to handle, reduces the chances of dropping it, and protects it to some degree from bangs, dings and chipping;

- Makes the stone more stable in use.

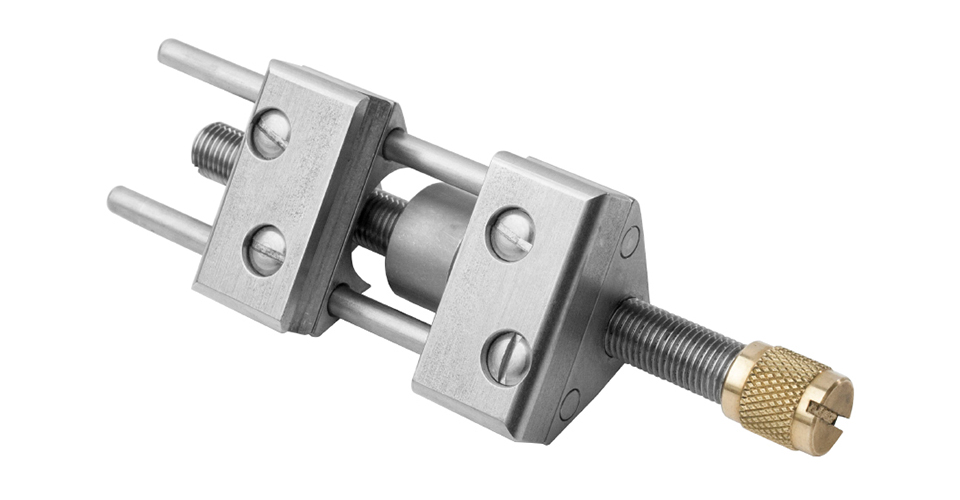

There are several options for materials from which to make a base. Probably the best material on paper is high-chromium stainless steel. I have never made a metal base but some friends have.

Most people, including me, choose to make their stone bases from wood; It’s the classic choice, but it has some downsides. For instance, it can warp, crack, rot and bugs might turn it into both home and dinner. So if you select wood be sure to choose a suitable species and develop a base design that sidesteps these shortcomings.

Most woods will work. I enjoy experimenting, so at various times I have made and used stone bases made from White Oak, Hinoki, Alaskan Cedar, Honduras Mahogany, Teak, and Ipe. Alaskan Cedar is an excellent wood for this purpose, but the best wood so far has been Ipe. It’s amazing: dense, but tough; It absorbs very little water and won’t crack or rot; Once stable, it doesn’t warp. At all. Bugs hate it. I love it.

So how did I learn about Ipe? An architect specified Ipe to deck an exterior engawa at a balcony on a commercial project I managed some years back, so I decided I had better investigate this material on the Client’s behalf. What I found in various installations in Tokyo and Yokohama was eye opening. A good example is the Ipe decking installed at Roppongi Hills Mori Tower in Tokyo. This building was completed in 2003. I worked out of a Client’s offices in this building off and on for 5 years.

The exterior wooden deck at RH is exposed to more nasty weather conditions than a postman, not to mention heavy foot traffic, but although it has turned grey, it has not split, warped, or rotted. The screws are still tight, and the surface shows very little wear despite several thousand people walking across it each day. Tough stuff.

So around 2010 when I bought my last replacement stone, I bummed a couple of decking cutoffs a local lumberyard had been using as stickers directly on the ground for years. The wood was wet and muddy, but still in good shape. I laminated them together to make the base pictured above. It has been better than any I made before that time.

A few years ago, I did another building with an exterior Ipe deck, this time in Yokohama. The decking subcontractor had mixed in two very dark, almost black pieces of Ipe that didn’t match and at all. At first glance I thought they were ebony. I had the subcontractor replace them for aesthetic reasons. Instead of throwing the boards away (they were already cut to irregular lengths), I scrounged them and made a second base for my favorite natural stone. Once again, excellent performance. Testing is complete.

The Stone Base: Design and Fabrication

Before you start cutting wood for your base, first flatten the bottom of your stone. It doesn’t need to be perfect, but you want at least 75% contact. A carborundum stone or diamond plate will work fine, but a cheaper and easier option is to rub the underside of the stone on a section of concrete sidewalk wet with running water from a garden hose. Be careful to choose a place with low foot traffic because the concrete can become polished and quite slippery as a result.

Depending on the shape of the stone, you may want to grind off rough spots and projections on the sides and ends too. Be careful when you do this to prevent spalling and other damage.

If the stone has visible cracks, let the stone dry in a warm dry location for a few days, then apply masking tape to both sides of the crack, and carefully soak a few drops of super glue deep inside. Hopefully this will prevent the crack from promulgating further.

Now that you have the stone’s final dimensions, make the base. Whatever wood you choose, select quartersawn pieces if possible for maximum stability against warpage, or laminate the base if not. Regarding dimensions, it needs to be thick enough to resist flexing much when pressure is applied during sharpening, and long enough to remain stable when pushed back and forth. Shape the ends so water runs off. Thicker is usually better than thinner.

Stone bases in Japan are typically made with a raised foot at each end as seen in the two examples here. These feet have several purposes. First, compared to a flat board, they help keep the base stable on uneven surfaces by spanning irregularities. I promise it’s very irritating to have the base rock in use. Second, they make it easier to correct wind in the base if it warps a little. And third, if the feet are laminated to a flat base, the difference in the grain helps to reduce potential warpage. It really does.

You can make the base as attractive or as utilitarian as you like, but avoid creating too many nooks and crannies for stone mud to collect in. The base pictured above retains the beaded profile cut into the wood’s upper surface to drain water from a deck, and it does drain water away from the stone effectively, but mud tends to collect in between the grooves. Not a fatal flaw, but it takes a few extra seconds with a brush to clean.

Be sure to chamfer or round-over all the edges and corners

Place the stone in the exact position on the base you want it to remain forever and mark the stone’s perimeter on the base.

Sand the wood directly underneath where the stone will rest. Don’t sand with the grain, but diagonally to create a cross-hatched rough surface. Completely remove any dust and wipe well with acetone or lacquer thinner.

Apply masking tape to the wood base at the outside of the stone’s outline.

Place the stone right side up on a flat surface and wrap, bend and fold a single strip of thin cardboard or manila file folder paper tightly around the stone’s sides and ends and secure it in place with masking tape to form both a skirt that seals tightly against the surface, and a reservoir to contain the epoxy used to glue the stone to the base.

Mix up some 2-part epoxy, enough the fill the reservoir at the stone’s underside plus a little extra. You want the epoxy to be thick, not runny. Any epoxy that will allow plenty of working time will do.

Force a little epoxy deep into the wood grain and sandpaper scratches with a small spatula or wood stick. Next apply the same epoxy to the bottom of the stone with your little spatula, and forcefully drive it into the nooks and crannies.

Pour the remaining epoxy into the reservoir you created at the bottom of the stone all the way to the brim.

Without letting the epoxy harden or flow out, flip the stone over and set it in the prepared position on the base in precise alignment with the masking tape outline you created earlier. Wiggle the stone a little to work any air bubbles out, and push the stone down hard until you sense it is contacting the wood.

Once the epoxy starts to set and become rubbery, but before it hardens, run a razor knife carefully around the stone’s perimeter cutting just a tiny bit into the wooden base, and then peel up and remove the masking tape and any epoxy squeeze-out. Be warned: this will be an armor-plated, DMV-style nightmare to cleanup later if you wait until the epoxy sets hard.

After the epoxy sets, finish the base with whatever material appeals to you. I soak mine in polyurethane thinned 100% and wet sand several times. I then wipe off any PU that remains on the surface. I guarantee you that any finish material you apply that remains on the wood’s surface will fail and look nasty after a few years of use.

I also like to apply a thin coat of Titebond Type III glue to the underside of the feet and base just for good measure. Does it make a difference? I dunno, but I’m a belt, suspenders, and full-harness kinda guy.

The Stone: Protecting and Reinforcing the Sides

It’s important to limit water from soaking into the stone’s sides along the sedimentary layers to prevent separation. In Japan it’s SOP to paint the sides with natural urushi lacquer, a toxic tree-sap that loves water and doesn’t easily chip. This material may be difficult to obtain outside of Japan or China, I fear.

Another option is an extremely high-solids (aka “goopy”) natural urethane paint made from cashew tree sap called “Cashew.” The material is used extensively in Japan as a replacement for nature urushi lacquer because it is less expensive, much easier to use, and more resistant to UV ray degradation. It’s made in Thailand and sold in Japan, but it may be difficult to obtain outside Japan. Or you can just use a commercial high-solids urethane.

To use Cashew or polyurethane, clean the stone and let it dry thoroughly. I mean really super dry.

Thin the Cashew or PU 10:1 with the special thinner Cashew sells, or high-quality professional-grade mineral spirits. The crap sold at Home Despot sucks.

Apply a coat of this thin finish with a brush and let it dry. It should dry quickly. Repeat at least 5 times. The mixture will soak into the stone to form a tight bond, seal cracks and pores, and serve as a primer for subsequent coats.

Whatever finish you use, it is best to apply the manufacturer’s recommended primer, or at least a thinned initial coat of the same finish to the stone’s sides and ends so it will penetrate thoroughly into the cracks and crevices further reinforcing the stone. Subsequent coats should adhere well to this primer coat if applied before it cures entirely.

Any color will work. I have a habit of painting any tools I might take to a demonstration or jobsite orange. It seems to stunt darwinian leg growth. Besides, orange was the color of the first GC I worked for back in Las Vegas many moons ago and it brings back pleasant memories. They painted everything orange.

One other thing some people do to reinforce their stones is to apply a strip or two of washi paper (traditional Japanese paper made from mullberry tree fibers) to the sides and ends using urushi lacquer, or whatever material they used for the stone. Despite being paper, washi is made from continuous fibers and is surprisingly strong.

Some people go so far as to use washi with printed images or calligraphy on it, and apply a clear coat of Cashew over the top so the printing is visible. I have never done this before, but it does look interesting.

Here is a link to a blog by an artist named Mr. Kobayashi about his sharpening tools with some photos of pretty stone bases. It is written in Japanese, but the pictures are informative. Not sure how well Google Translate would work.

The Stone: Storing & Transporting

Finally, I recommend you wrap your natural stone and its base in clean cloth or newspaper immediately after each sharpening session, while it is still wet, to protect it from dust and dings. After it has dried, store it in a box with a lid. A wooden box is nice, but a plastic one is more practical.

Here’s a link to a video about making a simple traditional Japanese tool box from softwood. If you haven’t made one of these before, they can be fun and quite useful. They guy in the video uses mostly powertools, and the construction is basic, but it’s all that’s really needed. This style of box was once standard among all construction trades in Japan but you don’t see them much nowadays because the plastic ones are more durable and much better suited to loading/stacking onto construction vehicles.

The high-impact plastic box pictured below is one I use for my sharpening stones. Manufactured by Reese in Japan, it has “Tool Box” heat stenciled into the side. Tougher than boiled owl and stackable, these containers will keep the contents dry no matter how hard it rains so long as the water level stays below the lower lip of the lid. Spring clips at each end do a great job of keeping the lid closed and attached even if the box tumbles off the back of a moving truck onto the road. The road rash will be bad, but the tools will stay inside. The problem is the truck following too closely behind…. Don’t ask me how I know. (ಥ_ಥ)

YMHOS

If you have questions or would like to learn more about our tools, please use the questions form located immediately below. Please share your insights and comments with everyone in the form located further below labeled “Leave a Reply.” We aren’t evil Google or incompetent facebook and so won’t sell, share, or conveniently and profitably “misplace” your information.

Leave a comment