A good tool improves the way you work. A great tool improves the way you think.

– Jeff Duntemann

Over the years your most humble and obedient servant has received many inquiries from Gentle Readers new to woodworking about what tools they should procure at the very beginning of their adventure. The internet is chock-a-block with both confounding confusion and beaucoup BS on this subject, some dribbling from amateurs and even more sprayed by marketing pukes and clickbait sages. Heretofore I haven’t really scribbled anything on the subject in this blog.

But now, at this fork in the crossroads, beginning with this article your penitent servant will share some thoughts about what tools a beginner needs to perform a lifetime of excellent woodworking, with minimum wasted time and funds, and the recommended priority for obtaining them.

Reluctant Advice

From this point forward I will be so bold as to make some suggestions about the the tools I recommend.

But first allow me to explain my viewpoint on the subject to help you gauge how much saltpeter and sulfur to mix with your charcoal, if you follow the allusion. You see, I enjoy giving Beloved Customers excellent choices in tools, but I’m allergic to giving casual advice. Why? Because even advice given honestly, with the best of intentions, and without profit motive often yields bad consequences. And sneezing.

In Proverbs 12:15 it’s recorded that Solomon the Wise (and disobedient) taught the following: “The way of a fool is right in his own eyes; But he who heeds counsel is wise.” Sounds good, I suppose, but does this mean that the man who’s convinced his honest decisions are correct, even after much study and experience, must still be a fool? Are only those who rely on counsel wise? What if the counselor he relies on is a blasted fool or a greedy, lazy influencer? Is all counsel equal in value?

King Solomon’s most famous descendant once said “Ye shall know them by their fruits.” Sounds like reasonable evidence-based judgment to me. So what were the fruits of Solomon’s advice? The record tells us that he thought his judgement so wise that he frequently ignored it on an epically immoral scale and with tragic, destructive results.

While less decisive than Proverbs but equally concise, I think Professor Tolkien’s insight on the subject may be even wiser, and so I have taken it to heart. In the Lord of the Rings he wrote “Advice is a dangerous gift, even from the wise to the wise, and all courses may run ill.”

Solomon’s fabulous famous folly aside, your humble servant has seen first-hand ostensibly wise advice purchased from reputedly wise “experts” at unjustifiably high cost run horribly ill too many times, so I dislike giving advice. And there’s the sneezing thing too, of course.

But since advice is what’s required, in this series of articles I will climb far out on a skinny tree limb to offer the following advice on two conditions. First, I insist Gentle Reader accept the value of this advice as worth no more than what you pay for it (nothing), and second, that any consequences that spring from your acting on this advice are entirely yours. Accordingly, I won’t be offended if, like Solomon the Wise, you decide to ignore it entirely and get yourself another hundred foreign girlfriends instead.

Anyway, back to the subject at hand.

Tool Categories

The following are the four basic categories, by function, of the tools I believe a beginner needs to possess to get started in a lifetime of woodworking, whether as a career or hobby. You’ll most likely need all the tools listed here eventually, but you won’t need them all at once to make excellent things from wood. The categories are as follows:

- Measuring, Marking and Layout Tools:

- Sawing Tools

- Chiseling Tools

- Planing Tools

Of course, depending on your projects, you’ll need tools that don’t fit neatly into these four categories, such as those used for processing trees and making lumber, nailing, boring/drilling, screwing, gluing, clamping, laminating, sanding, edge treatment, assembly, and finishing. When it comes to these other categories of tools, I can only encourage Gentle Reader to rely on your prodigious innate common sense.

Each list is divided into two tiers. The first tier includes absolutely necessary tools. The second tier lists essential tools you will eventually need, but can get by without until later.

So let’s begin by examining the minimum measuring, marking and layout tools every beginner needs. I will deal with the other categories in future posts. If I’ve forgotten anything critical, please let me know in the comments form below.

Essential Measuring Tools (Tier 1)

While chopping, sawing, carving, joining and planing get all the attention, final results in woodworking (and all physical trades for that matter) can never be better than one’s skills at measuring, marking and layout, so woodworkers and builders need to own the related tools and master them.

By no means sexy jobs, both ancient and modern history provides endless examples of poorly performed measuring, marking and layout work buggering cost, schedule and quality goals with a barge pole wrapped in barbed wire. No wonder these jobs have historically been assigned to the most experienced and intelligent craftsmen. The simple tools included in this category will serve you well in any handwork activity, not just woodworking.

One caveat. I have listed a few tools below that are modern precision tools beginners should own and learn to use skillfully, but I know a few purists who find such tools violently repulsive. The truth is that the more experience one obtains, the less one tends to rely on absolute measurements in millimeters, inches, or cubits, and more on relative precision. But possessing the tools to perform precise measurement is nonetheless necessary if you plan to do quality work.

Necessary Measuring Tools (Tier 1)

You’ll need the following essential measuring tools from day one.

1. Quality Tape Measure with an accurate sliding hook (check to make sure it’s not sloppy). Size will depend on the projects you plan to undertake, but 2-4 meters is a minimum useful length for cabinetry, furniture making and joinery. Get a reputable name brand, with a warranty. Avoid like an Asian giant hornet with flaming hemorrhoids any cheapo crap made in China, India or Vietnam. Tape measures are a bit delicate and don’t last forever, so treat yours gently and check it frequently against your precision straightedge for accuracy and damage. Do not rely on it for great precision. Since ancient times the folding scale has been thought superior, a sentiment with which I agree in the case of some jobs. But in general nothing beats a quality steel tape measure for most quick and dirty measuring tasks.

2. Precision Straightedge (12”/300mm long) with accurately, deeply etched graduations. This is a precision measuring and layout tool. Good quality graduations are useful for precisely indexing and guiding layout tools such as pencils, pens, divider points, and a marking knife. Hardened stainless steel is ideal for durability. Best if it’s made to high quality standards (JIS, etc.). You’ll use it not only for measuring and checking the accuracy of your other tools, but more frequently for checking that surfaces are flat and free of wind (twist). If treated with respect, it will serve you well for a lifetime.

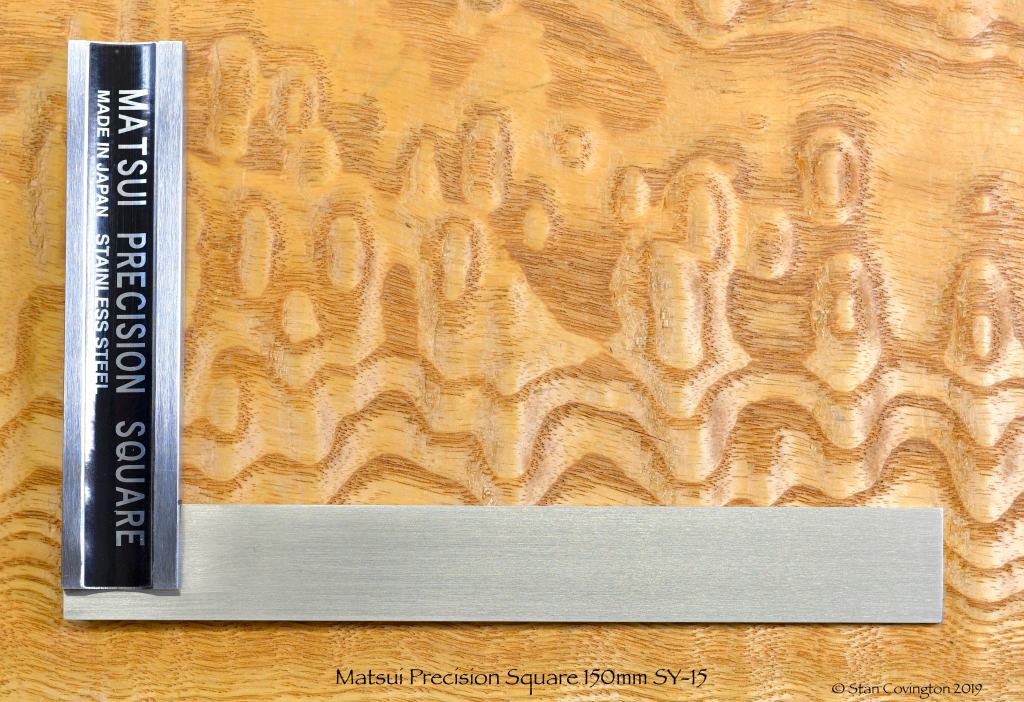

3. Try-square (see item 2 below). The handy dandy try square has many uses as a measuring tool, but rather than making numerical measurements, its most important job is checking that right angles of components, tools and assemblies are indeed 90˚ , a check one must make constantly and quickly when planing/machining the components of furniture, joinery and cabinetry and casework not to mention setting up portable and stationary power tools. Most try-squares sold nowadays are poor quality Chinese or Indian junk that are out-of-tolerance when new. I too like pretty tools and realize that a plain stainless steel square doesn’t look as cool as more traditional squares with rosewood stocks and brass fittings, but the blade and the stock should both be made of stainless steel and should be solidly welded to each other, not glued or pinned. Best if the blade is hardened. Graduations are not necessary. Get this essential tool wrong and all is lost.

Necessary Measuring Tools (Tier 2)

4. 1-meter stainless steel precision straightedge. This tool needs to be certified by a reputable standards organization, such as Japan Industrial Standards Committee (JIS), NIST: National Institute of Standards and Technology (USA); UKAS United Kingdom Accreditation Service (UK); DIN (Deutsches Institut für Normung), etc.. Why does certification matter, and why is it worth the extra cost? Fraud and deceptive marketing are more common now than ever, with many well-known manufacturers taking a page from Chinese Best Industrial Practices of bait, lie, mislable & switch. In the case of a tool certified by an organization such as NIST, JIS, DIN etc. with a valuable reputation to lose, you are much less likely to be fleeced by quality crooks. Indeed, this tool, along with the 12″/300mm straightedge and try square listed above must be accurate enough to serve as one of your own in-house “standards.” It must not only be extremely straight when new and stress-relieved, to avoid future warping, but it must have deeply, uniformly, precisely-etched graduations. It’s OK if it spends most of its life hanging from a nail on the workshop wall, because there will be times when it will be critical for quickly for checking surfaces for flatness and wind, layout, assembly, dimensioning boards and fettling handplanes.

5. Caliper Gauge: This gauge can be of the vernier, dial or digital variety, whichever type you like and can afford. Once again, buy a certified product. This tool is useful for precisely and quickly measuring, comparing and laying out distances and dimensions. Some are sold with carbide tips convenient for directly scratching layout arcs/lines/points in harder materials such as metal or stone. Will you use it constantly? No, but for those tasks where it’s needed, nothing works as well or as quickly. Quality vernier calipers cost much less than the dial or digital variants, and are not as delicate, but take more time and concentration to use well. Once again, nothing made in China, India, Vietnam, Cambodia, etc. When in doubt, I buy Mitsutoyo.

Necessary Layout & Marking Tools

Try Square (same as see item 3 above). This tool is absolutely indispensable for layout and marking of joinery, cabinetry, and furniture work. 100-150mm is a handy size for furniture work. Even if your workshop has been thoroughly purged of pernicious pixies this tool will be dropped, and will wear out in-use, so a useful one will have a welded (not just pinned) connection between the thinner blade (aka beam or tongue) and the stock. And, this is important, the blade will be made of hardened stainless steel. Graduations are totally unnecessary. Used for marking 90˚ lines and checking for squareness. Matsui Precision makes the best one I am aware of after much searching and hands-on experience in the field.

7. Framing/Carpenter’s/Builder’s Square.

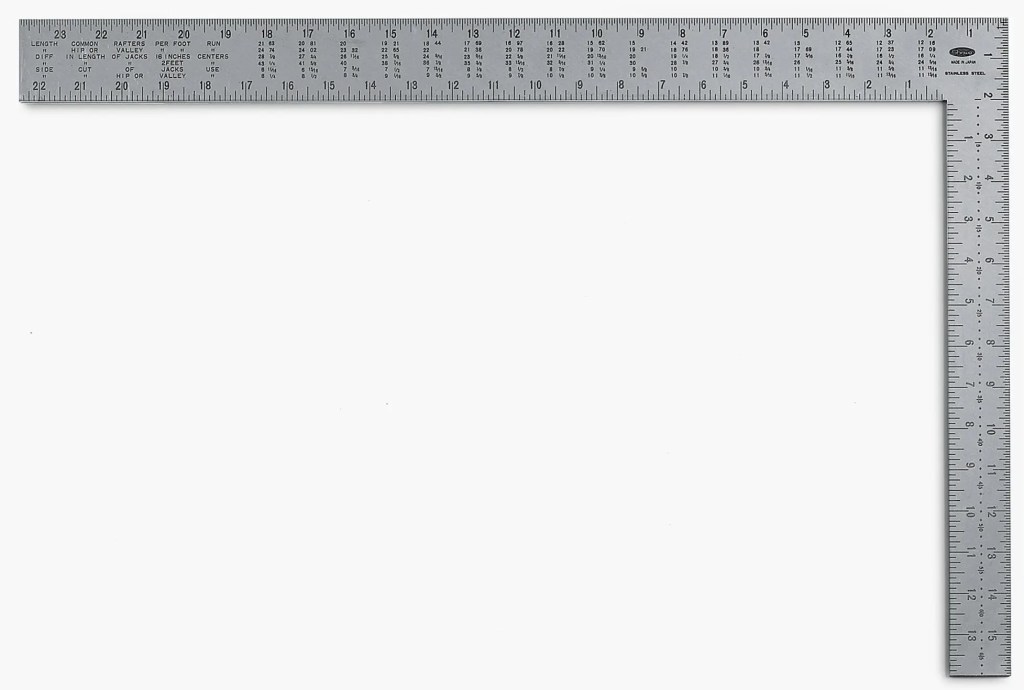

Essential for checking lumber, laying-out and marking of larger joints, casework, checking square of larger joints and assemblies, working with doors, panels, and plywood, and many other tasks. Regarding materials, carbon steel squares are heavy and always turn red and go away, so I don’t recommend them if you have a choice. Stainless steel is more durable, but still heavy and costlier. Aluminum will suffice. You may need to true it, but this is easily done with a hammer, punch and file. Just ask me how when you think it’s necessary. This is a tool with a long history you should be proud to own. In all nations more than a few centuries old, the carpenter’s square has been associated with stability, honesty, righteousness and order, all traits a craftsman should seek to foster in himself, his family and his crew. In Japan, this tool was traditionally extremely expensive and was considered the craftsman’s “spirit” in the same way the sword was revered as the warrior’s spirit by the warrior caste. Indeed, in past centuries, stepping over a carpenter’s square resting on the floor or even ground was seen as a mortal offense resulting in bloodshed at times. Such emotional sentiments did not extend to other carpentry tools. The Japanese version of this tool goes by several names written several ways including “kanejaku,” “magarijaku”(written 曲尺or 矩尺), “sashigane”指矩, and several other names. Don’t ask me why. Unlike the Western square of uniform thickness, the better Japanese kanejaku have a variable cross section for less weight/greater rigidity. Being thinner, smaller, more flexible, and much lighter in weight, the Japanese square is handier to transport and use in the field. Of course, it has a couple of disadvantages such as not handling longer/wider boards as well, and being more difficult to control because it’s more flexible. Horses for courses, of course, so I own and use both types.

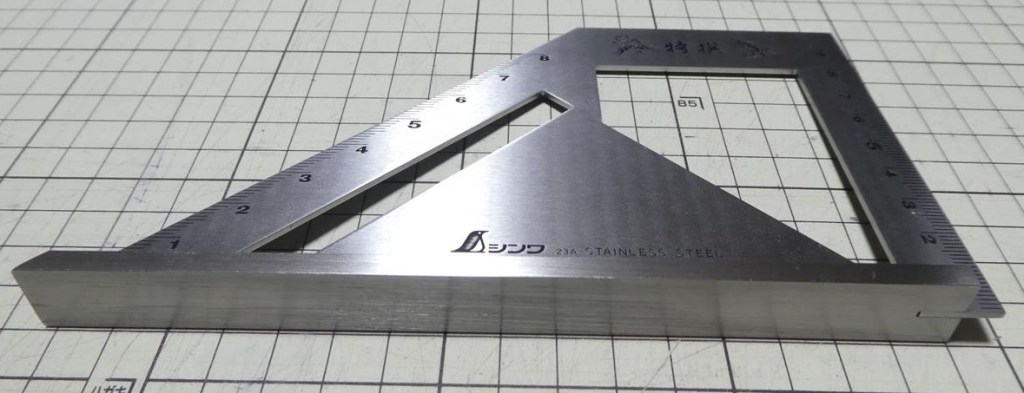

8. 45˚ Stainless Steel Layout Tool or quality speed square for laying-out miters. An accurate combination square will work too, but such tools are relatively expensive and quite fragile. The Shinwa tool shown below is cheaper, much tougher and absolutely reliable.

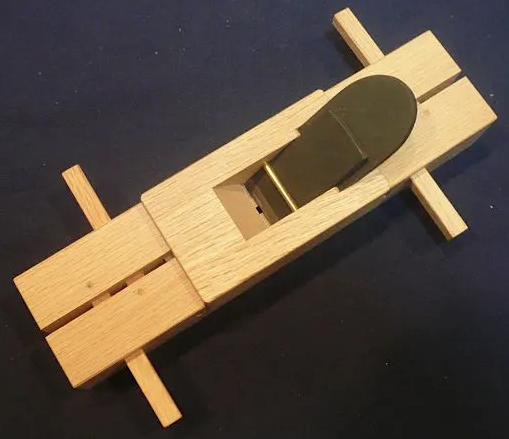

9. Marking Gauge: There are many types of marking gauges, most of which the craftsman can make himself without special tools or machinery. Perhaps this will be the subject of future articles. In any case, you will need at least 2 types of gauges.

The classic type has a single pin or blade to cut/scratch a single line with each stroke and has been around since Moses wore gator skin loafers. You can make versions from scrap wood, nails, or scrap steel easily yourself.

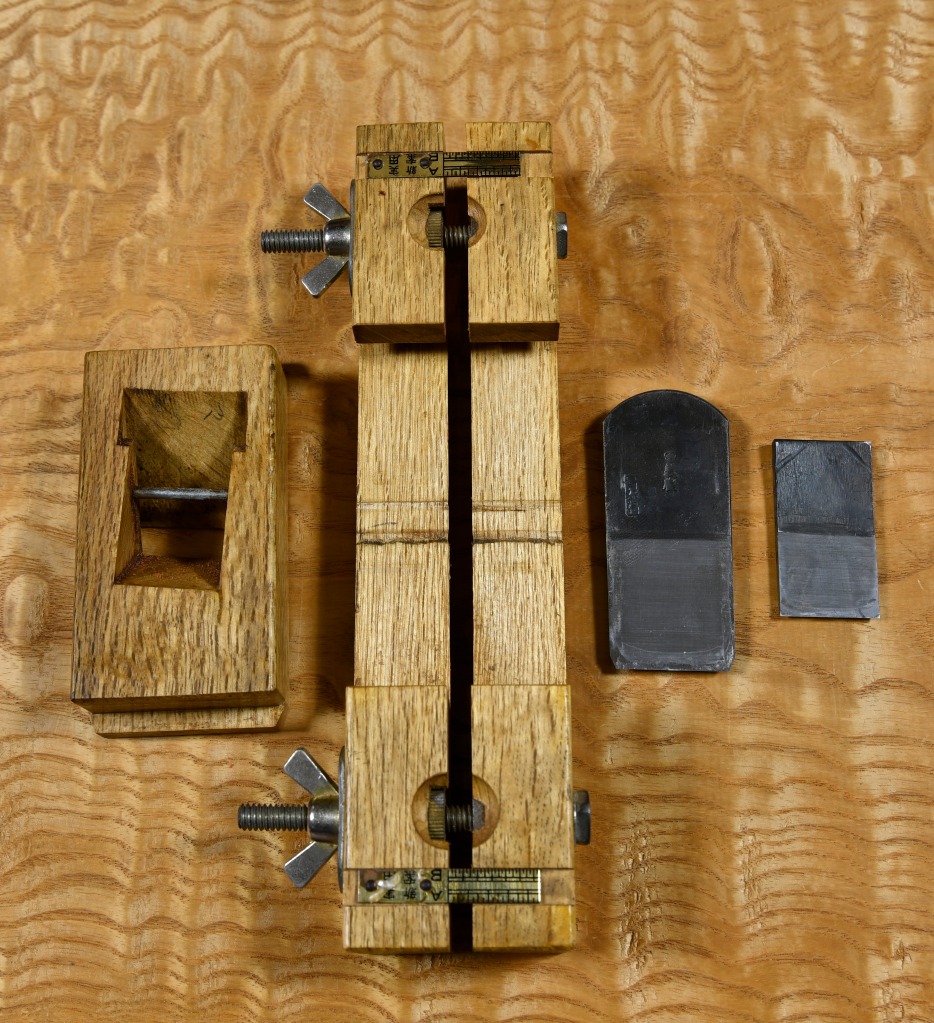

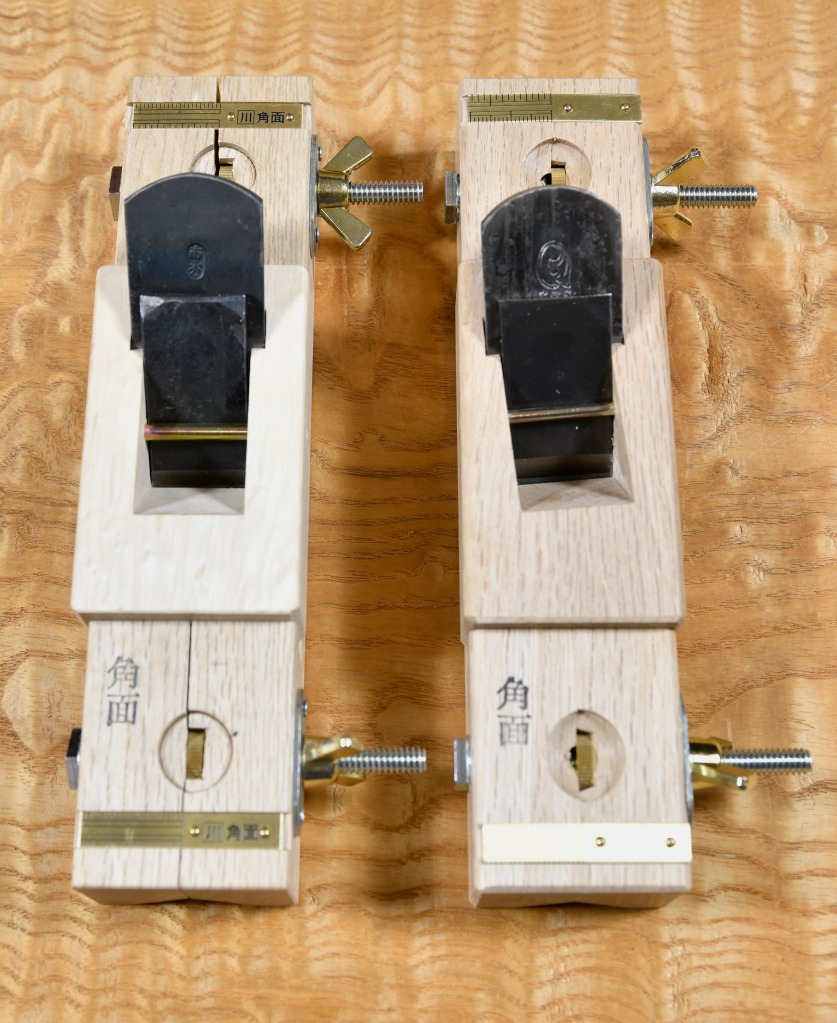

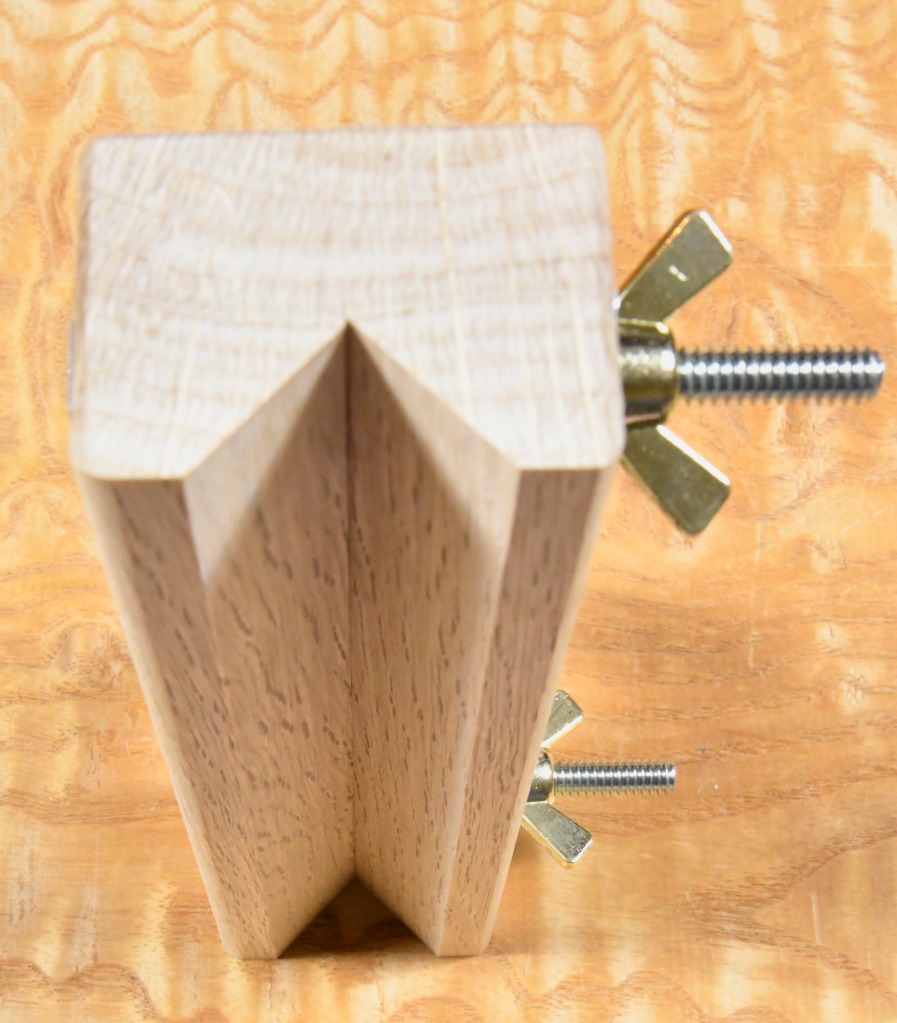

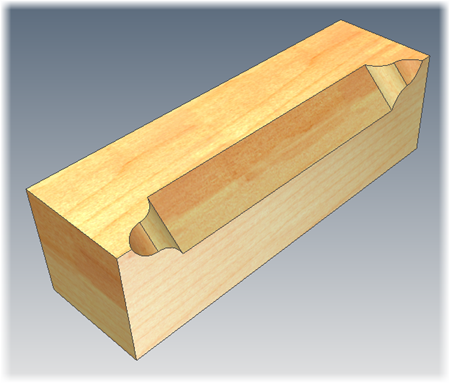

The second marking gauge you should have is called a “mortise gauge.” This tool has two pins or blades to make 2 parallel lines, at a set distance from each other, with a single stroke. It’s especially suited for quickly and precisely marking mortises and tenons and installing hardware. I prefer the Japanese version of the mortise gauge called the “kamakebiki” (sickle mortise gauge shown above) which has two L-shaped steel blades, easily adjusted and easily resharpened. A handy tool indeed.

Having multiple marking gauges on-hand will help to minimize the time you must spend resetting/adjusting the pins/cutters, a principle key to performing precise work consistently because every time a gauge is reset, error creeps in, sure as pigs are made from bacon. Marking gauges are simple tools easily mastered, but don’t underestimate the importance of owning a few and mastering them completely.

The Titemark gauge is an excellent tool, not only because it cuts consistent lines, but because it can be quickly and precisely set using a single hand and no tools. The only downside is the depth of cut is shallow and the cutter is easily damaged.

10. Carpenter’s Pencil. Useful for the same marking jobs as a plain pencil, but if one sharpens its wider lead to a chisel edge, it will be more durable (won’t break as easily) and last much longer than a standard pencil.

11. Divider/Compass. An essential tool for layout used to quickly and accurately transfer distances from straightedge or layout stick etc. to a workpiece. Of course, it can perform all the classical geometrical tasks that have made this tool essential to skilled craftsmen, architects and engineers worldwide for millennia. A spring divider is adequate, but finances permitting, Starrett 92-6 or 92-9 dividers shown below are worth every penny. I always have at least two on-hand to minimize the lost time and inaccuracy frequent resetting entails.

12. Ballpoint Pens: Not often thought of as a precision layout tool, inexpensive ballpoint pens are more durable than pencils and can make a permanent mark or line of consistent width without needing to be resharpened. Too wide for accurate layout, you say? Practice perfectly sawing in half the centerline of a line drawn with a pen and you’ll change your tune.

13. Marking Knife and/or Scriber. Instead of leaving a line of ink, chalk or graphite on the surface of a board, these tools cut or scratch a permanent line into the surface of material being worked into which divider points and the blades of cutting tools such as chisels, saws and even planes can be indexed quickly, reliably and without the need for expending much attention, greatly increasing speed and confidence in one’s layout. Essential tools. Here’s a Link to an article on the subject.

14. Inkpot and/or Chalkline: For making long straight lines on wood, concrete, steel, gypsum board, etc. The article at this LINK contains more details

15. Colored Marking Pens or Lumber Crayons: Marks made with colored marking pens or lumber crayons, while not precise, are helpful for speedily marking/identifying the orientation and/or relative position of parts, pieces and components in an assembly. For instance, a blue stripe, or two parallel black lines on the end of a part or tenon, might be drawn to indicate right-hand, or North, or front direction in an assembly. I sometimes draw an arrow to orient the front of the assembly or to indicated the direction/location of a reference surface or part, etc. Of course, drawing the cabinetmaker’s pyramid is essential for joinery and casework. The marking convention you choose is, of course, up to Gentle Reader, but having one and using it will help your work go faster and with less confusion, especially if you must set the part aside for a few days or even months. Lumber crayons are especially useful for marking lumber for dimensioning and planing.

Storage, Transportation & Protection

With the exception of the 1-meter long straightedge, and that only because it’s inconveniently long and I want to protect it from dents and dings, I always keep these measuring, layout and marking tools located in the handiest place in my toolchest when I’m in my workshop, or in my portable toolbox and/or toolbag when I’m working in the field.

If you carry these tools outside the workshop, and intend them to be lifetime tools, I recommend you make a simple case for each tool, of cardboard perhaps, to cushion them in your toolbox to help retain precision, to keep them from dinging each other, and help to them last longer. Only then can you reasonably expect a long, mutually profitable relationship with these good friends.

In the next installment in this swashbuckling adventure we will consider the next category of tools the beginner needs: Saws.

YMHOS

If you have questions or would like to learn more about our tools, please click the “Pricelist” link here or at the top of the page and use the “Contact Us” form located immediately below.

Please share your insights and comments with everyone in the form located below labeled “Leave a Reply.” We aren’t evil Google, fascist facebook, or thievin Tik-Tok and so won’t sell, share, or profitably “misplace” your information. If I lie may pug pirates make me walk the plank!

Leave a comment