The Road goes ever on and on,

Down from the door where it began.

Now far ahead the Road has gone,

And I must follow, if I can,

Pursuing it with eager feet,

Until it joins some larger way

Where many paths and errands meet.

And whither then? I cannot say.The Road goes ever on and on

Bilbo Baggins

Out from the door where it began.

Now far ahead the Road has gone,

Let others follow it who can!

Let them a journey new begin,

But I at last with weary feet

Will turn towards the lighted inn,

My evening-rest and sleep to meet.

Your humble servant has received many inquiries over the years from Honorable Friends and Beloved Customers (may the hair on their toes never fall out!) about how to setup, maintain and use Japanese planes to which I have gladly responded when the request for information was made politely.

The Japanese hiraganna handplane is an elegant tool with a simple yet deceptively sophisticated design, not a difficult tool to master once one understands its unique design principles and learns a few basic techniques easily taught in person; But it can be frustrating to master them using only written guidance.

But despite my hesitation heretofore, I believe the time has come to begin this journey. I pray Beloved Customers will have the courage to accompany me down this road that goes ever on and on until we reach the lighted inn. When we arrive, the first round of root beer will be on me, so drink up!

Let’s begin the journey by examining some relevant terminology. Don’t forget your handkerchief!

Terminology

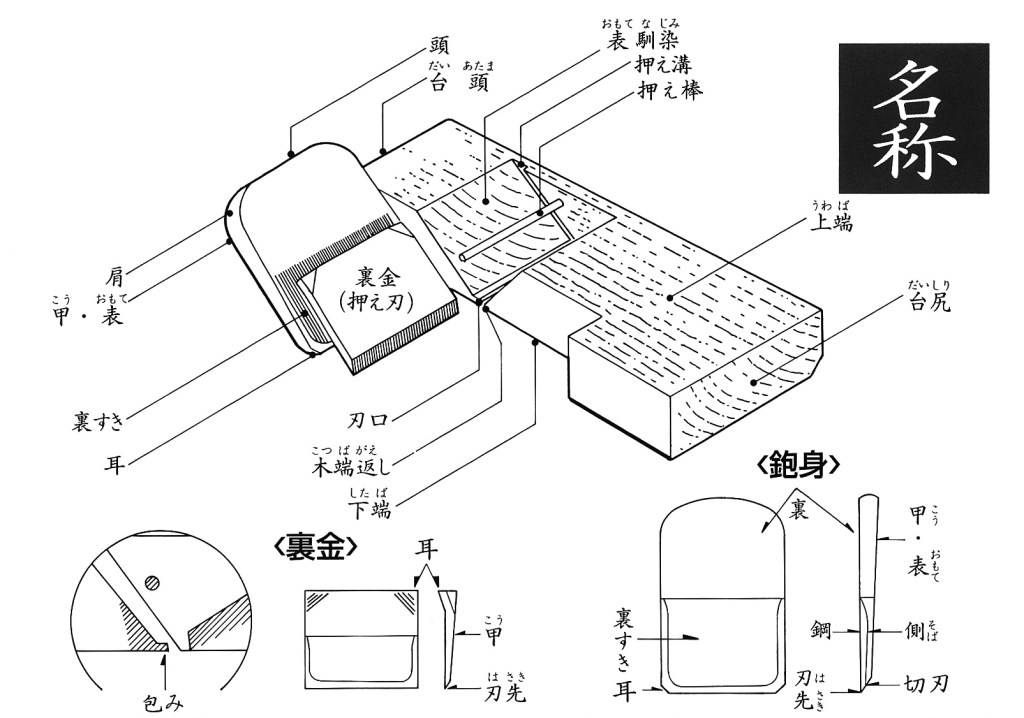

In this and subsequent posts in this series your humble servant will not attempt to educate Beloved Customers in all the Japanese language terms for every part of the plane, nor will I use Japanese conventions for describing handplanes, since that would be about as useful as ice-skates on a hog. Instead I will use standard English language terms wherever possible. There is an illustration below that shows the various components and features along with Japanese language labels for those interested.

Indeed, since the plane is a relatively recent tool in the Japanese woodworker’s toolbox, and has a much longer archeological history in the West, it seems silly to use more Japanese words than absolutely necessary to describe something that did not originate in Japan, and can easily be described in English. I will, however, venture to describe some of the more common general terms specific to the Japanese handplane.

I am neither a lawyer nor a government employee and so see no need to make things more confusing than necessary. I humbly apologize in advance to any purists who enjoy being confused.

The standard handplane in Japan, and the one used for creating and/or smoothing flat surfaces (versus rabbet, chamfer or molding planes) is called the “hiraganna,” pronounced hee/rah/gahn/nah, and written using the Chinese ideograms 平鉋 , without emphasis on any part of the word.

The first character 平 is pronounced, in this case, “hira” (there are at least 6 standard pronunciations for this character as it is used in Japan) and means “flat.” makes sense, right?

The second character 鉋 , written “kanna” in the Latin alphabet and pronounced “kan/nah,” means “plane” (as in “handplane”). This character is comprised of two standalone characters combined to make a single character, a common practice in the Chinese and Japanese languages. The one on the left side, 金, means gold or metal, while the one on the right, 包 means “to wrap.” Kinda sorta makes sense; Almost hardly.

The character for kanna was not invented in Japan but is said to have been used in China since the Táng period AD618 – 907, although the tool it represented at the time was a multi-blade scraper of sorts and not a handplane.

Comparison Between Western and Japanese Wooden-bodied Bench Planes

If your humble servant may be permitted a brief digression on a personal subject, I would like to clarify a point of some small relevance to this explanation of the Japanese handplane.

I have at times been called a Japanophile, and although I confess to being fond of the mountainous islands and the wonderful people of Japan, the years I have spent living in Japan, and my ability to read, write and speak the language were not born of some starry-eyed infatuation with or even simple admiration of Japan, but by practical service obligations, educational pursuits and my work in the construction industry.

My point is that I prefer Japanese tools and techniques when I think they are superior, and by the same token prefer Western tools and techniques when I believe they are superior. Consequently, I like to flatter myself that I can provide a relatively unbiased viewpoint, one which will come into clearer focus near the end of this article.

Of course, those who prefer Western tools and techniques above all others will say I am biased towards the Japanese way, while those who prefer Japanese tools and techniques above all others will insist I am biased toward Western tools and techniques. There is no way to win such an argument, so Beloved Customers must judge for themselves. Anyway, back to the subject at hand.

A detailed treatise comparing wooden-bodied Japanese handplanes to steel-bodied Western handplanes would be an extravagant waste of Beloved Customer’s precious time, so I will resist the temptation. But I would be remiss to not point out that Bailey-pattern steel-body handplanes do have a few serious advantages over wooden-bodied planes in general, while wooden-bodied planes in general, and Japanese hiraganna planes in particular, have several serious advantages over modern Bailey-pattern planes the thoughtful woodworker should understand.

Some of the advantages of modern steel-bodied Baily-pattern planes over all wooden-bodied planes include the following:

- The steel plane’s body is unaffected by seasonal humidity changes and therefore warps less and requires less fettling. This is a huge advantage;

- The steel plane’s sole is harder and wears slower than a wooden sole, and therefore lasts longer and requires less fettling. Also, since the sole wears slower, the mouth does not easily become wider as soon, and seldom if ever needs to have a new mouth inlet. This is another huge advantage.

Both of these advantages can have a humongous impact on the effectiveness and productivity of the tool over the years.

Some of the advantages of Japanese wooden-bodied planes over steel-bodied planes include the following:

- The wooden body is not as easily damaged as a traditional cast-iron steel-bodied plane’s body which will bend and/or fracture if dropped onto a hard surface (the ductile cast iron used in some high-end planes nowadays is a significant improvement in this regard). Fracturing has been the bane of cast-iron-bodied planes since the beginning. This is a huge advantage;

- The plane’s Owner can modify, repair, or make a replacement wooden body exactly to his preferences quickly and inexpensively;

- The wooden sole is softer than a steel sole and therefore is not only less likely to scratch the surface being planed, but will tend to burnish it instead;

- The wooden sole is easier to true, fettle, and even modify;

- The wooden body is lighter in weight and therefore both less tiring to use and easier to transport;

- Japanese handplanes have lower profiles so they take up less volume in the toolchest and/or toolbag, and are easier to store and transport;

- Japanese handplanes have few if any screws and no levers so adjustment is simpler, more intuitive, and entirely dispenses with the clumsy, often sloppy mechanical linkage common to mass-produced Bailey-pattern steel-bodied planes;

- And finally, the biggest advantage of the Japanese handplane is, (drumroll please), the blade. If hand-forged from high-quality steel and properly heat-treated, will become much sharper, stay sharper longer and will be easier to sharpen than the blades of modern steel-bodied Bailey-pattern handplanes. No contest. Your humble servant believes the blade’s performance is the most important aspect of a handplane because, after all, it is a cutting tool, not a paperweight (although I admit to having a pretty little LN No.1 benchplane in white bronze I place on my desk and use as a paperweight. My associates here in Japan can’t figure out what it is so I tell them it’s for shaving kiwi fruit (ツ)).

Allow me to expound a little further on the advantages of the Japanese handplane:

Blade Performance:

The Japanese planes we carry have hand-forged laminated blades made from specialized high-carbon tool steel to meet the performance expectations of professional woodworkers in Japan. The crystalline structure of this steel once made into a blade by our blacksmiths is fine-grained and uniform. Blades are exceptionally hard at 65~66Rc, and remain sharp a long time while being easily sharpened.

There was a time in centuries past when Western blades were of near equal quality, but no longer. Sadly, the blades of most Bailey-pattern planes manufactured nowadays are made of high-alloy steels for which quality control can be easily automated, but which were never intended for handplane blades. These steels are undeniably tough, but won’t become very sharp initially, quickly dull, and are, relatively speaking, an “evil screaming bitch” to sharpen (pardon the excessively-technical jargon).

Blade Appearance:

While it used to be that Western wooden-bodied planes had interesting maker’s marks stamped in their blades, such is no longer the case. Japanese planes, on the other hand, make a point of having decorative engraving, stampings and surface treatments applied to their blades for a significantly more interesting presentation of the blacksmith’s art than the plain, boring sanded steel of modern Western planes.

Reliable Blade Retention:

The blade of Japanese handplanes is wedged tightly into two grooves in the side of the body preventing shifting and rotation, and providing reliable settings. Most modern Western handplanes rely on a relatively complicated and less-secure blade retention and adjustment mechanism.

Simplicity:

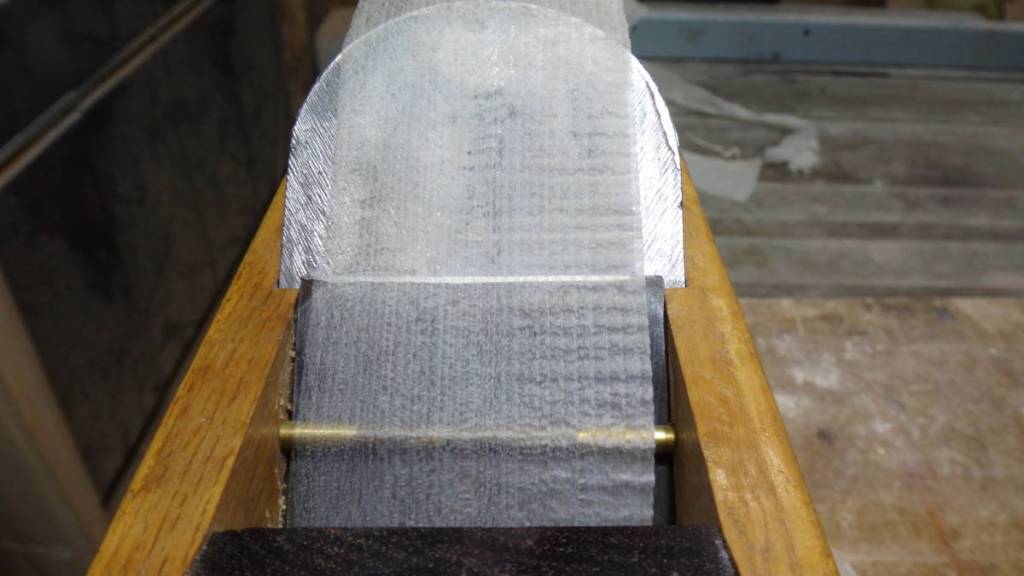

The standard Japanese hiraganna plane has at most 4 components: The body, blade, chipbreaker (uragane), and chipbreaker rod. Planes with adjustable mouths will have more parts, but those are not standard planes. Screwdrivers and wrenches are not necessary for adjusting or disassembly of Japanese handplanes. Western planes often, but not always, have at least 21 and sometimes more components and require tools to field-strip.

And all the parts in Bailey-pattern handplanes have built-in slop which grows worse with use and often makes adjustment irritating and sometimes even unreliable.

The Japanese hiraganna does not have a separate wedge or a mechanical assembly securing the blade in-place. Instead, the blade itself is wedge-shaped, narrowing in thickness from the head to the cutting edge, so that it fits tightly into two grooves, one cut into each sidewall of the mouth opening, for a secure fit, an elegant, simple and utterly reliable design.

Lower Profile and Reduced Weight:

Japanese hiraganna have thinner bodies and a lower profile than Western Bailey-pattern planes and even Western wooden-bodied planes. Accordingly, they weigh less and take up less space in the toolbox.

While there are times when your humble servant appreciates the extra momentum a heavier steel body affords when making deep cuts, those instances are limited to specific applications. The rest of the time the extra mass is like a bloated and corrupt government agency: a pointless burden.

In all other applications, the lighter weight of the wooden-bodied Japanese hiraganna plane is a blessing.

Smoother Surface

Where wooden-bodied planes of all types excel is the superior finish they leave on the wood they are used to plane. That is not to say steel-bodied planes cannot create a perfectly smooth surface, but it is the nature of steel to develop dings and burrs in-use that frequently leave scratches in the wood they are planing. And while a wooden sole will burnish a wooden surface, the best steel can do is rub it.

Western Steel-bodied Handplanes: The Right Tool for the Right Job 適材適所

There is a saying in Japan I am told that comes from the boat-building tradition where many types of wood are used for the various components in a quality vessel, and it goes something like this: Tekizai tekisho 適材適所 meaning: “The right wood for the right place.”

Your humble servant is a pragmatic son of a gun, and a firm believer in using the best tool available to achieve the best results possible. Accordingly, it would be exceedingly foolish to insist that Japanese handplanes are always the best tool for every planing job. Indeed, I have used a combination of both Bailey-pattern steel-bodied handplanes and Japanese-style handplanes for many decades, selecting the best tool for the specific job at-hand. So what steel-bodied planes do I believe excel?

Scrub Plane

I have found the Stanley No.40 furring plane and especially its more modern equivalent the Lie-Nielson 40 1/2 scrub plane to be superior for removing material when dimensioning lumber (making it thinner and flatter).

This is an extremely simple plane with a narrow, thick blade 1.450″ x 3/16″ ground to a large curvature and a big mouth designed to hog lots of wood. The handles make it easier to leverage body weight into the cuts.

In the case of the LN model, the blade is A2 steel, a material developed originally for dies, not plane blades, a tool steel that will never become especially sharp, and which dulls quickly, but once it has dulled to a certain point simply keeps on cutting, seemingly forever. And while the blade may become dented and dinged, it will not easily chip, perfect for the rough work of dimensioning dirty and stone-infested rough-sawn lumber.

The ductile iron sole of the LN product will be of course be scratched by dirt and stones hidden in the wood, but who cares? Better a steel scrub plane than the white oak of my Japanese planes. I consider Lie-Nielson 40 1/2 to be an essential plane in my toolchest.

Block Plane

The steel-bodied Western block plane is also an essential tool IMHO.

There are of course Japanese planes with similar dimensions, of lighter weight and with better blades, but they all have one weak point, namely the area right in front of the mouth becomes scratched and grooved and wears quickly because block planes are often used to trim and clean edges a job applies a high point load on the mouth. The fix used in Japan is to inlet a brass plate at the mouth. We carry small planes with this feature when new.

Also, I use my block planes for finish carpentry and installations which involves working around hidden finish nails, little pieces of steel that damage wooden bodies and hard blades, but which a steel block plane shrugs off.

I own several block planes, being fond of experimenting with tools, but have found the Lie-Nielson No. 60-1/2 rabbet block plane with nicker to be the one most useful for me.

Jointer Plane

Another Bailey-pattern steel-bodied plane I consider to be excellent is the jointer plane. When a young man I owned an old Stanley No.7 jointer plane I bought at a flea market, but it fell from the back of my 1966 VW van many moons ago and suffered the fate common to most old cast-iron planes, breaking both the body and my heart in half. I bought the Lie-Nielson version many years later and have been pleased with it’s performance (my expectations were never very high).

It’s a monster at 22″ long and weighing 8-1/4 lbs. I hate the heck out of the A2 steel blade. To make things worse, the sole was warped when I bought it new, so I had to spend hours flattening it on sandpaper and glass. Why do I like it? The cast ductile iron sole is tough and never warps (or at least hasn’t since it came to me). The extra length makes it especially stable for cuts ending or starting off the piece of wood I am planing. When I have a large surface such as a table to flatten, my No.7 may not cut like a dream or be easy to use, but it always makes the job go quicker.

Conclusion

In this post we have briefly touched on the history, terminology, advantages and disadvantages of the Japanese hiraganna plane. We have also compared it to Western planes, and concluded with several examples of Western handplanes your humble servant believes to be superior to their Japanese counterpart.

I hope you will agree that the Japanese handplane is a tool worth mastering if only because of the excellent work it can help you execute. Besides, they’re a lot of fun.

In the next post in this story of supernatural intrigue and inter-dimensional romance we will discuss how to properly adjust a Japanese hiraganna plane without hurting its feelings.

YMHOS

If you have questions or would like to learn more about our tools, please click the “Pricelist” link here or at the top of the page and use the “Contact Us” form located immediately below.

Please share your insights and comments with everyone in the form located further below labeled “Leave a Reply.” We aren’t evil Google, fascist facebook, or thuggish Twitter and so won’t sell, share, or profitably “misplace” your information. If I lie may my jointer plane break in half and bust my toes.

Leave a comment